A remarkable thing is happening before Special Counsel Jack Smith’s federal grand jury investigating the removal and mishandling of classified and other highly sensitive documents by Trump and his aides.

Three of Trump’s attorneys, who were assisting him by gathering documents, interfacing with investigators, and making representations about the non-existence of further documents, have now appeared to testify before it.

They include:

- Christina Bobb, who signed a now infamous affidavit claiming there were no further documents at Mar-a-Lago responsive to the government’s subpoena;

- Evan Corcoran, the lawyer who supposedly performed the search and drafted the affidavit but had Bobb sign it; and most recently

- Alina Habba, who was recently ordered, along with her client Donald Trump, to pay nearly $1 million in sanctions for filing a frivolous lawsuit against Hillary Clinton and other former officials.

Three Trump lawyers.

They join a long list of Trump lawyers who faced repercussions after working with Trump. How should we consider this development and what happens next?

Let’s take another dive into the world of attorney-client privilege and an important concept related to it called the “crime-fraud” exception.

Then just for yucks, let’s apply what facts and precedent we already have and take a stab at whether Smith likely will prevail.

Lawyers are almost never witnesses.

Lawyers serve a vital and special role in our adversarial judicial system. Clients should be able to talk to their lawyers candidly and confidentially so they can receive sound legal advice and prepare for their cases accordingly.

That’s why the idea of having your lawyer, to whom you have likely spilled your guts, come in and testify against you seems almost shocking. If it happened frequently, no one would feel comfortable talking to their attorneys, and our justice system would grind to a halt.

That’s why to even call one of the defendant’s lawyers as a fact witness for the prosecution is a gutsy and rare move. To bring three of them in is nearly unheard of.

As Los Angeles Times Senior Legal Affairs columnist and former U.S. Attorney and Deputy Assistant AG Harry Litman noted, Department of Justice guidelines require “lots of process and approval to pull attorneys in front” of the grand jury, and “obviously Smith got it here.”

So how does this happen?

When a lawyer acts solely as legal counsel, listening to the facts and reviewing the evidence then advising and taking action on a client’s behalf, there’s generally no issue. That’s how it’s supposed to work.

But once that lawyer oversteps the line and begins instead to assist the client in actual criminal activity, whether wittingly or even unwittingly, the government can call the lawyer as a witness to the crime.

But to get them to squawk requires a further, even more difficult step.

The crime-fraud exception.

We all got a refresher course on the crime-fraud exception to the attorney-client privilege last year when Trump’s lawyer, John Eastman, sought to block production of his emails as part of the January 6 Committee’s investigation.

A federal court in California ruled that it was likely that Eastman and Trump together committed two federal crimes: conspiracy to defraud the U.S. and obstruction of an official Congressional proceeding.

Emails that Eastman sent and received in furtherance of this crime were therefore not shielded from discovery; the crime-fraud exception had “pierced” the veil of the attorney-client relationship, and he had to turn a number of them over.

It’s now understood that at least one of Trump’s lawyers on the classified documents investigation, Evan Corcoran, refused to answer questions put to him before the grand jury by prosecutors by asserting attorney-client privilege.

Special Counsel Smith is now seeking to pierce that privilege by arguing that Corcoran’s communications with Trump were made in furtherance of a crime, namely obstruction of justice. The standard of proof here is “by a preponderance of the evidence,” meaning greater than 50 percent.

So to force Corcoran to testify, prosecutors will need to convince the judge that it is more likely than not a crime was committed by Trump and that Corcoran’s communications with him were part of that crime.

Note that we don’t yet know whether Trump’s other attorneys asserted the privilege and are facing a similar motion. Such things are generally kept confidential while they proceed before a grand jury.

But there is a source within the case talking to the press about Corcoran. In most cases, it is someone on the defense side; here Corcoran, like Mike Pence, may want to signal publicly that he is doing everything he can to not have to testify against Trump.

Is Smith likely to succeed against Corcoran?

Here is what we know.

The National Archives went back and forth with Trump and his team for nearly a year seeking to recover documents that it learned Trump had taken with him. This resulted in the return of some 15 boxes of documents, some of which were marked classified.

That set off alarm bells with the archivists, who referred the matter to the Justice Department which then convened a grand jury to investigate the matter.

That grand jury issued a subpoena for any further classified documents that might still be located at Mar-a-Lago. On June 3, 2022, Jay Bratt, the chief of the counterespionage section of the National Security Division at the DoJ, visited Mar-a-Lago and met with both Corcoran and Bobb.

Corcoran had supposedly gone through materials himself to identify responsive documents to turn over in advance of that meeting, and he also showed Bratt the storage room where the materials were kept.

The attorneys ultimately turned over a Redweld folder containing more classified documents. Importantly, they also provided a written statement, drafted by Corcoran and signed under oath by Bobb, that all classified materials had now been returned.

The Department soon learned this affidavit was false.

There were still many more classified documents still at Mar-a-Lago, as security camera footage appeared to show. That resulted in a warrant for a search of the property and the removal of another 26 boxes of documents in August of 2022, including hundreds of documents marked classified.

This means one of two things.

Either Trump misled Corcoran into believing that no further documents existed (for example, by explicitly telling him that, or by actively hiding the documents from him), or Corcoran was in on the lie and assisted Trump in hiding them from the government.

In either case, the crime of obstruction of justice is implicated: Trump either used Corcoran to unwittingly further his obstruction, or he worked with Corcoran who knowingly furthered it.

It turns out there is strong precedent in favor of piercing the attorney-client veil when false statements by an attorney are laid bare. In fact, this would not be the first time the question of the crime-fraud exception on a matter involving a Trump aide has come before the judge in this matter, the Hon. Beryl Howell, the chief district court judge in the D.C. circuit.

Paul Manafort’s lawyer tried to assert the privilege when called as a fact witness in Manafort’s criminal case, but the government successfully showed that an exception should be made and the lawyer be required to answer specific narrow questions because it had been the lawyer who had submitted letters containing false and misleading information to the Department of Justice.

These questions included who were the sources for each of the false or misleading submissions.

The same argument could be used to force Corcoran to testify, given that the statement that he drafted and had Bobb sign and submit to Jay Bratt was also demonstrably false, as the subsequent search resulting in hundreds of more classified documents revealed.

Prosecutors should be able to ask Corcoran who the source of that information was. For example, did Trump tell Corcoran there were no more classified documents, and did he just take his word for it?

Or did Corcoran himself look and still not find anything, which could only really happen if Trump hid the documents from him or kept him out of certain areas like his bedroom and office.

This all leads to what I’ve always thought was the most dangerous claim for Trump: an obstruction charge under 18 U.S.C. 1519. Juries might have trouble making sense of whether something ought to be marked classified, or whether it was somehow “declassified,” even if only by Trump’s faint brain waves.

The fact that President Biden and former Vice President Pence also had classified documents at their homes makes it hard to argue that Trump should be prosecuted solely for having them in his possession, while they should not.

But a cover up is far easier to understand. If Trump instructed Corcoran to lie on his behalf, and Corcoran testifies about that before a grand jury, that makes for a pretty solid case for obstruction.

I should note that obstruction is no minor crime.

It carries a prison sentence of up to 20 years, so the statute has real teeth. I have a sense that Corcoran participated in this cover up unwittingly and will not want to go down for that solely to protect his client.

We’ll see whether Corcoran goes back in to testify before the grand jury in the near future.

That would tell us the motion by Jack Smith has succeeded at least in some important measure.

@kellyclarksonshow/Instagram

@kellyclarksonshow/Instagram @kellyclarksonshow/Instagram

@kellyclarksonshow/Instagram @kellyclarksonshow/Instagram

@kellyclarksonshow/Instagram @kellyclarksonshow/Instagram

@kellyclarksonshow/Instagram @kellyclarksonshow/Instagram

@kellyclarksonshow/Instagram @kellyclarksonshow/Instagram

@kellyclarksonshow/Instagram @kellyclarksonshow/TikTok

@kellyclarksonshow/TikTok @kellyclarksonshow/TikTok

@kellyclarksonshow/TikTok @kellyclarksonshow/TikTok

@kellyclarksonshow/TikTok @kellyclarksonshow/TikTok

@kellyclarksonshow/TikTok @kellyclarksonshow/Instagram

@kellyclarksonshow/Instagram @kellyclarksonshow/Instagram

@kellyclarksonshow/Instagram @kellyclarksonshow/Instagram

@kellyclarksonshow/Instagram @kellyclarksonshow/TikTok

@kellyclarksonshow/TikTok @kellyclarksonshow/TikTok

@kellyclarksonshow/TikTok @kellyclarksonshow/TikTok

@kellyclarksonshow/TikTok @kellyclarksonshow/TikTok

@kellyclarksonshow/TikTok

@machinegunkelly/Instagram

@machinegunkelly/Instagram @joeyyoey/Instagram

@joeyyoey/Instagram @sherbetglassart/Instagram

@sherbetglassart/Instagram @_unsailyas_/Instagram

@_unsailyas_/Instagram @sara.kachilika/Instagram

@sara.kachilika/Instagram @happy_tea_mum/Instagram

@happy_tea_mum/Instagram @killl_me_slowly/Instagram

@killl_me_slowly/Instagram @ariannasteger/instagram

@ariannasteger/instagram

rPolitics/Reddit

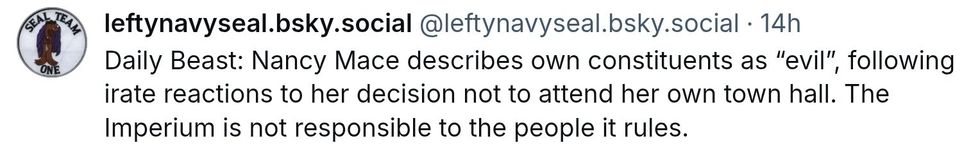

rPolitics/Reddit @leftynavyseal/Bluesky

@leftynavyseal/Bluesky rPolitics/Reddit

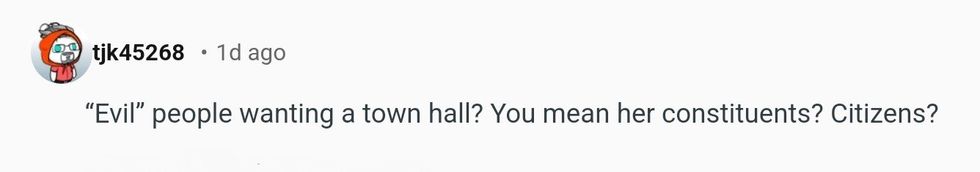

rPolitics/Reddit @skippyoz/Bluesky

@skippyoz/Bluesky rPolitics/Reddit

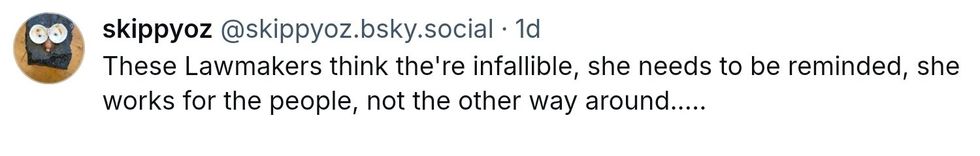

rPolitics/Reddit rPolitics/Reddit

rPolitics/Reddit rPolitics/Reddit

rPolitics/Reddit

jordi baste robot GIF by No pot ser! TV3

jordi baste robot GIF by No pot ser! TV3 sing schitts creek GIF by CBC

sing schitts creek GIF by CBC Well Done Ok GIF by funk

Well Done Ok GIF by funk Two Face Ernst GIF by ZWEIMANN

Two Face Ernst GIF by ZWEIMANN