Officials at the Red Cloud Indian School on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota brought in a team of specialists to excavate a basement on its campus. The school is a private Catholic school open to residents of the surrounding area.

The school serves about 600 Indigenous students from kindergarten through high school. In 2019, the school launched a Truth and Healing initiative to reconcile its problematic past. Red Cloud alumnus Maka Black Elk (Oglala Lakota) was appointed as executive director of Truth and Healing in 2020.

\u201c\u201cThe Catholic Church needs to recognize that honesty, being forthright and vulnerable are far more powerful and more healing than being reticent, restrictive and closed,\u201d said Maka Black Elk, Oglala Lakota, executive director for Truth and Healing at Red Cloud Indian School.\u201d— Rep. Ruth Anna Buffalo (@Rep. Ruth Anna Buffalo) 1664480883

Testimony from a former student pointed to potential graves in a basement at the school that was once part of the Holy Rosary Mission.

The school was founded by the Jesuit and the Franciscan Sisters in 1887-1888. The Jesuits were invited by Oglala Lakota Chief Red Cloud—for whom the school was renamed—to provide education to his people.

Chief Red Cloud hoped the Jesuits would help the next generation of Lakota to survive in “the White man’s world.”

Despite this cooperative beginning, the school became part of the national government policy to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children into White culture. Children were often sent to boarding schools hundreds of miles or more from their families.

The Indian Boarding School Policy made attendance at boarding schools mandatory—even for children who lived in White communities—if one of their parents was Indigenous.

Students allowed to return home typically spent 10 months of the year at the boarding schools.

Parents who didn't voluntarily surrender their children had them removed by force by agents of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Those children were often sold to White families as servants, laborers or novelties in response to their parents' noncompliance.

Such documented practices contributed to the creation of the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978.

Students were stripped of all semblance of their culture once they arrived at school. At the beginning, anything they arrived with or wore was confiscated and boys had their hair cut.

Speaking their language or practicing their culture was harshly punished with beatings, confinement and withholding of food.

Children not allowed to return home during the summer or holidays were often placed on work details for White families or at factories or businesses or loaned out to wealthy White benefactors as novelties.

Any money earned went to the schools to "support their mission."

Children who showed athletic promise—like famed Sac and Fox athlete Jim Thorpe—were placed in semi-professional sports leagues to generate more income for schools. Most schools also had workshops, kitchens or laundries to generate income and train students for menial labor positions after graduation.

Half of each day was devoted to schooling with the other half to jobs around the mission including laundry, cooking, farming and carpentry.

An estimated 100,000 Indigenous children attended mandatory boarding schools in the United States. Many of those schools were run by Catholic religious orders.

At Holy Rosary, years of records kept by German Franciscan Sisters at the mission totaled the number of children who died each year.

Multiple forms of abuse were rampant.

Though some portions of the federal government's assimilation policy ended as early as the 1930s, it took until the 1970s before the United States began to turn control over Indigenous education to individual Tribal governments.

During the 1960s the government eased enforcement of mandatory boarding school attendance for Indigenous children who lived off reservation. In 1969, Holy Rosary was renamed after Chief Red Cloud. By 1980, the school phased out dormitories and became a day school only.

In the years since then the school has worked to overcome its past.

The school reversed its curriculum, offering Lakota language and cultural studies classes.

In 1993, Jesuit Father General Peter-Hans Kolvenbach issued an official apology to the Lakota saying:

“I realize that we, as Jesuits, have at times been the source of some of [the Lakota's] pain."

"For that we are deeply sorry.”

The search for children's remains in unmarked graves on campus is the latest part of that effort.

Since May the school has gathered testimony from former students and hired a full time archival researcher to examine school records currently housed at Marquette University—a private Jesuit research university in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Red Cloud school officials also commissioned experienced ground-penetrating radar technician Marsha Small (Northern Cheyenne) to conduct a geophysical survey of potential sites identified by eyewitnesses in search of unmarked graves.

\u201cExcavation begins at Red Cloud Indian School for small graves seen in a basement years ago as part of a Truth and Healing effort to uncover the school's boarding school history https://t.co/kUPzr3RIxv\u201d— ICT (@ICT) 1666125283

Small told Native News Online:

"It's heavy, because I'm doing heavy work."

“Regardless of if we find a body there or not, I’m treating it like a crime scene."

"That’s what this all is."

\u201cThey've begun the search for our young relatives at Red Cloud Indian School on Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. \n\nThey say they're treating it like a crime scene.\n\nGood. That's exactly what it is. \n\nhttps://t.co/HPaPzxuUEo\u201d— Frances *Deadly SoverAuntie* Danger (@Frances *Deadly SoverAuntie* Danger) 1666118937

Maka Black Elk stated:

"We are opening the doors that we formally kept closed as an institution."

“We're opening our records and archives to be thoroughly investigated, in terms of analyzing what's there, and making those records public."

"In terms of the gathering of testimony, we're not discriminating against people telling their story. We're not picking and choosing the alum who tell their stories and only wanting the positive ones."

"We're hearing them all. With the [ground-penetrating radar], we're not investigating ourselves."

"We've invited an external team to come and provide their expertise and meet a demand of the community and seek the truth of what’s there."

Excavation at the first identified location—a basement of one of the campus buildings—yielded no remains.

***

Author/Editor note: My Father—Edward Franklin Christnot—attended Holy Rosary Mission Indian boarding school on Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in the 1940s and 1950s. From the time the Assimilation Acts were passed by Congress and the Oglala Lakota were forced onto reservations, all of my paternal family was forced to attend Holy Rosary until my generation.

\u201cAki\u010ditaki\u014b wi\u010dayuoni hup\u00e9.\n\nMy Father and I, September 1969.\nEdward Franklin Christnot, Chief Warrant Officer, Vietnam veteran, United States Navy\n\n#VeteransDay2020\u201d— Amelia Mavis Christnot (@Amelia Mavis Christnot) 1605075474

Everyone, that is, except for my Great-Grandfather Edward Gerry. Edward was shipped by railroad as freight to Haskell Institute for Indians in Lawrence, Kansas.

My Father shared stories about getting in trouble with the Fast Horse and Archambault boys and a Jesuit Priest telling their basketball team not to "act like a bunch of wild Indians" when they stopped at a diner on the way home from a game. If I listened to just my Father's stories, he and my Uncle Ralphie and Aunties Tino (Marcella) and Bert (Alberta) had a grand time at boarding school.

But as an adult, he cut his Mother out of his life for years because she "sent" hime to boarding school. Grandma Sally Marie Gerry Christnot Freitag had no choice if she wanted to keep her children—just as her Mother Helena Larvie Gerry had no choice when Grandma Sally was surrendered to the same school her Mother Helena was forced to attend.

Three generations with no good choices.

My Auntie Tino told us about laying alone in an infirmary for a month with many other children while she suffered from pneumonia. Even though her Sister and two Brothers were also at Holy Rosary, they weren't allowed to see her or even know how she was.

In her words, children either recovered or died. Holy Rosary's records showed a high rate of death from illness and disease just as other boarding school records and cemeteries indicated. There were also many "accidental" deaths.

Our Grandparents weren't told Aunty Tino was sick. The children in the infirmary were fed but not given much else for care.

Auntie Tino was 6-years-old at the time.

\u201c@Ruth_HHopkins My Great-Grandmother Helena in her official boarding school portrait, Oglala Lakota of the Oceti Sakowin.\u201d— Amelia Mavis Christnot (@Amelia Mavis Christnot) 1622600650

Our family also had a saying—"Other schools had playgrounds, we had cemeteries." I don't know if it was a common saying, or just something in our family.

For many Indigenous people in the United States and Canada, the discovery of children's remains at boarding schools—called residential schools in Canada—was not a revelation.

It was common knowledge.

Still, we survived.

Now it is time for the next generation to thrive.

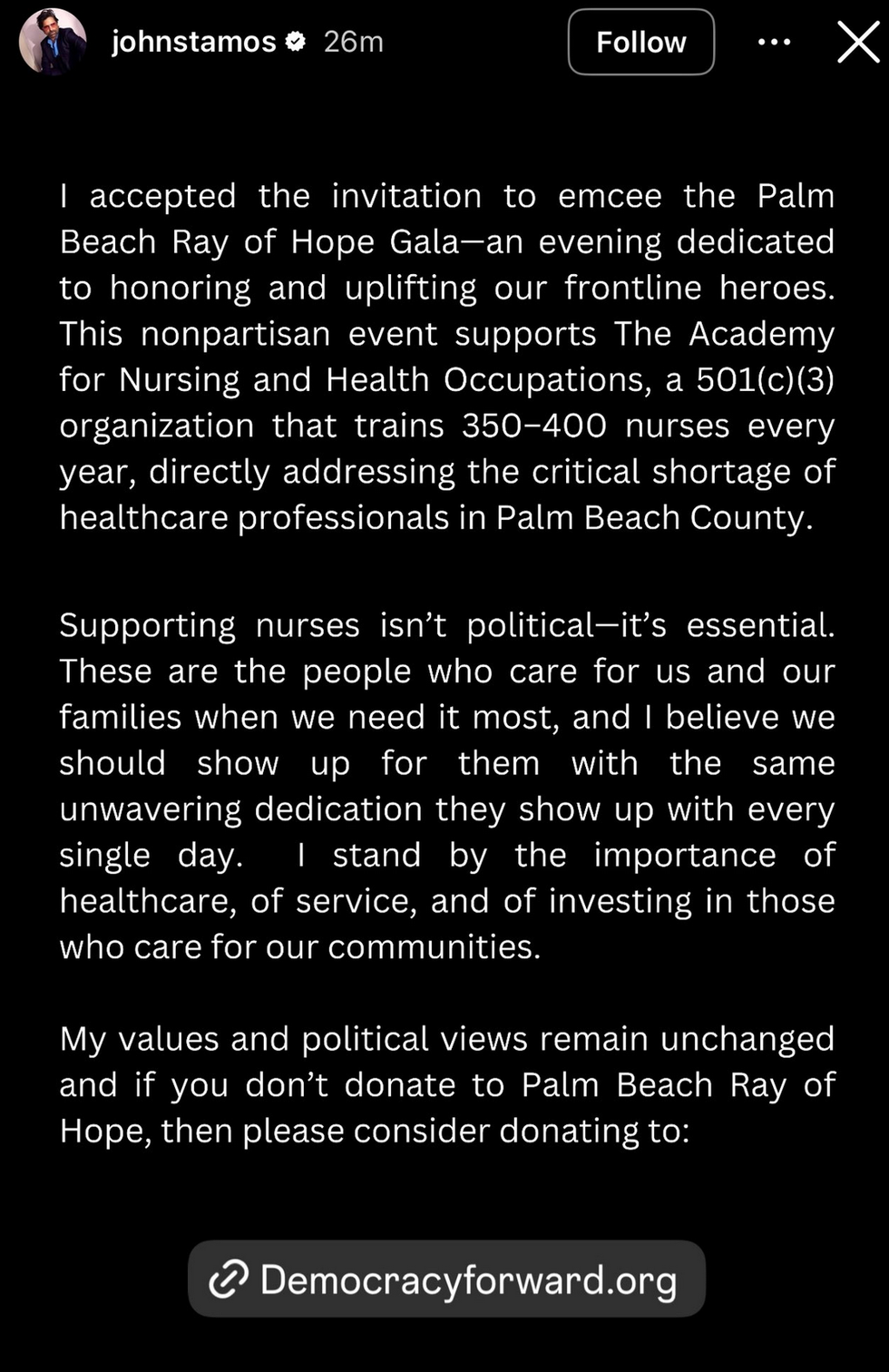

@johnstamos/Instagram

@johnstamos/Instagram

@mtgreenee/X

@mtgreenee/X

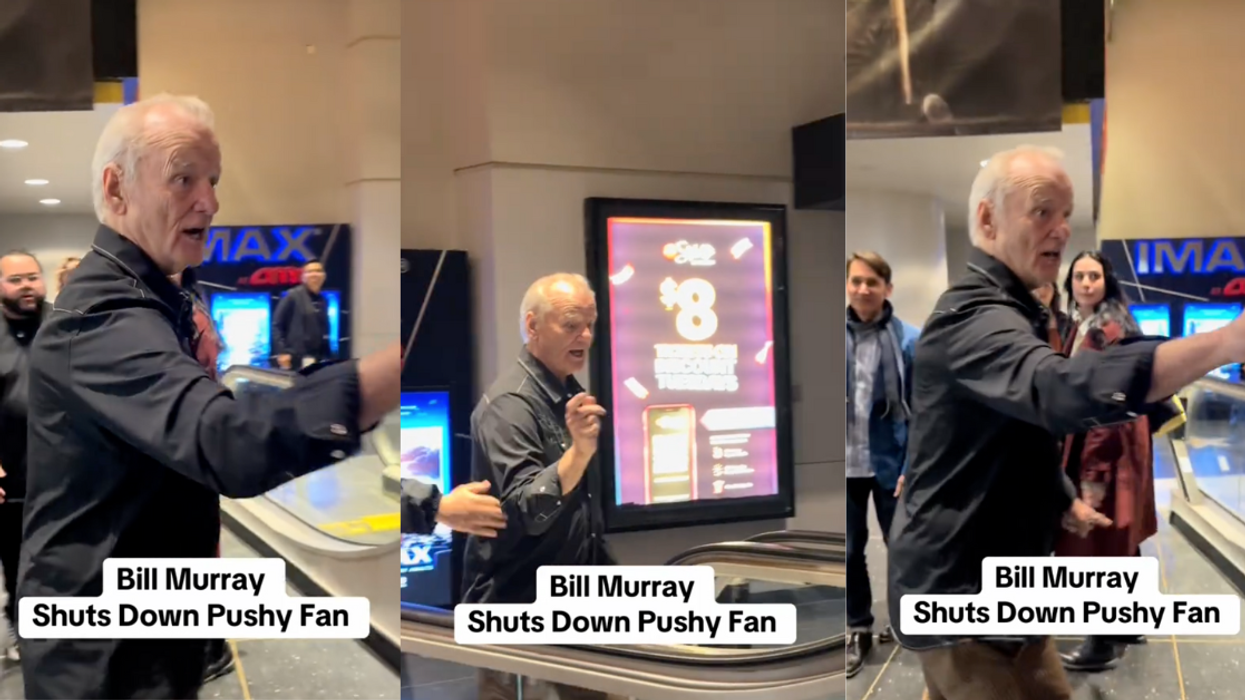

@nulllnvoidd/TikTok

@nulllnvoidd/TikTok @warrent711/TikTok

@warrent711/TikTok @terrance.n1/TikTok

@terrance.n1/TikTok @slghtr9/TikTok

@slghtr9/TikTok @itsmittymoon/TikTok

@itsmittymoon/TikTok @kokoanddaisy/TikTok

@kokoanddaisy/TikTok @jdr1959/TikTok

@jdr1959/TikTok @mandy24787/TikTok

@mandy24787/TikTok @crilan2015/TikTok

@crilan2015/TikTok @orutisu88/TikTok

@orutisu88/TikTok