Octopuses and humans have next to nothing in common, right? Scientists just discovered that we're not nearly as different as we thought and the secret to our similarities lies in ecstasy.

The last time we had any evolutionary traits in common with the octopus was 500 million years ago.

Our nervous systems are set up in completely different ways.

Humans have a central nervous system while octopuses have a decentralized nervous system. They have control centers for each of their arms that are separate from their brain.

The one similarity between humans and octopuses is the fact that we both have a gene for a protein that binds serotonin, the "feel good" molecule, to the brain.

Gül Dölen, a neuroscientist from Johns Hopkins University, and Eric Edsinger of the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts recently studied the effects of MDMA on our 8 armed friends and found that we have more in common than one would imagine.

Octopuses are known to be shy, solitary animals. Ecstasy (MDMA) is known for its effects of extroversion on humans. Dölen and Edsinger sought out to find out if the drug would have a similar effect on octopuses since MDMA has an effect on serotonin.

They had a control group of 7 Octopus bimaculoides which they put in lab tanks.

The tanks were filled with MDMA infused water. After soaking up some of the drugs, they were moved into a chamber with 3 rooms — a central room, a room with a male octopus, and a room with a toy.

Sober octopuses avoided the other octopus, staying true to their typical antisocial behavior.

However, after the octopuses had spent time in the ecstasy bath, they spent more time with the male octopus.

They were also reported to touch the other octopus in a curious rather than aggressive manner.

Dölen and Edsinger also noticed dosage differences.

The first time they did the test, the MDMA levels were too high. According to Dölen, the octopuses

"freaked out and did all these color changes."

Once they got the dosage right, Dölen said,

"They're basically hugging the [cage] and exposing parts of their body that they don't normally expose to another octopus. Some were being very playful, doing water acrobatics or spent time fondling the airstone [aquarium bubbler]."

Experts, like Judit Pungor, have found the study to be

"an incredible paper, with a completely unexpected and almost unbelievable outcome."

She continued saying,

"To think that an animal whose brain evolved completely independently from our own reacts behaviorally in the same way that we do to a drug is absolutely amazing."

Many other people were fascinated.

For some people, the study was overwhelming.

Others found their thoughts octopi'd by jokes.

This major insight into the fact that social behavior originates at a molecular level is inarguably fascinating. Dölen also thinks the study shows the true power of drugs.

"People are beginning to recognize that these drugs are powerful tools for understanding how the brain evolved. They're such strong activators of these behaviors. It's not subtle."

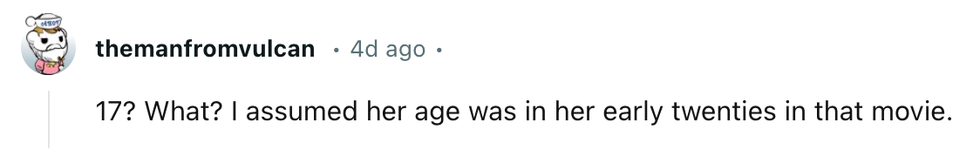

@themanfromvulcan/Reddit

@themanfromvulcan/Reddit @buffysmanycoats/Reddit

@buffysmanycoats/Reddit @jadelikethestone/Reddit

@jadelikethestone/Reddit