Empathy—that ability to imagine how another person feels and share an emotional experience along with them—is praised as an ideal of human behavior. After all, one of the alleged hallmarks of a true psychopath is that they can’t feel empathy or don’t come by it naturally. Without empathy, how can we understand what the marginalized and the suffering go through? Social scientists believe that empathy originates, evolutionarily, as a series of “prosocial” behaviors, essential glue that helps humans stick together for increased survival.

Yet, more recently, psychologists and neuroscientists alike have begun to take a radically different stance on the empathy-is-good line of thinking. In fact, over-empathizing might be making usemotionally burned out and unwell, leading to such states as “compassion fatigue,” or “secondary trauma,” which affects first responders and caregivers at higher rates. In these states, a person can begin to feel numb, depressed, anxious, or even inexplicably angry.

However, it isn’t only those who rescue and help others on a regular basis that are sensitive to “catching” the pain of empathy. The truth is, we all are. You’ve felt it when reading a news story circulating on social media about a war-torn country, or kids living in poverty, or the victims of a natural disaster come across your feed. At first you feel sad, then depressed, and then, you may have the urge to turn it off, look away—because it hurts to empathize.

In 2004, social neuroscientist Tania Singer was the first person to put a subject into an fMRI machine and look at whatempathy did to the brain. Sixteen romantic couples took turns receiving mild electric shocks to elicit a pain reaction in the brain. First they measured what happened when the volunteer received a shock, and then they measured what happened to their romantic partner when they heard their partner receive a shock. While the shock itself naturally lit up the pain centers of the person receiving the shock’s brain, hearing a romantic partner receive a shock lit up a different kind of pain center—known as “afferent pain” or emotional pain, part of the “empathy for pain network.” In other words, empathy hurts.

Singer’s work also found that empathizing with the physical or emotional pain or stress of strangers can also elicit distress in an onlooker. Emma Young writes forNew Scientist, “That is backed up by experiments in which, for example, people who watched a 15-minute TV newscast reported increased anxiety afterwards, with their anxiety only decreasing after an extended relaxation exercise.”

Over-empathizing can lead to all kinds of negative emotional outcomes. “People who experience more empathic distress in their daily lives are more likely to become aggressive when provoked even towards an innocent person,”said Olga Klimecki, University of Geneva in Switzerland.

And, in fact, no one may truly be immune to empathy, not even those allegedly unfeeling psychopaths. In 2014, Christian Keysers, a neuroscientist at the Netherlands Institute for Neuroscience in Amsterdam, studied the brains of psychopaths in relationship to empathy. When they first showed psychopaths images with no instruction on how to feel, the volunteers’ brains did not show much activity in the brain areas connected with empathy.

However, Keysers then asked these volunteers to consciously empathize with images they saw and the results were significantly dramatic—their brain responses were identical to those of the normally feeling, empathy-enabled control group’s. Young wrote, “In other words, even if your default empathy state is ‘off,’ you can turn it on when desired.” That was an eye-opener says Keysers: it seemed clear that a spectrum of empathy could exist in all individuals.

Since her 2004 study, Singer has begun to study the difference between empathy and compassion. She built upon earlier research by Richard Davidson, a professor of psychology and psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin, Madison where Buddhist monks were put in an fMRI machine and exposed to sounds such as women screaming in pain. The monks, who, through meditation, have been shown to have the ability to manipulate their neural empathy circuitry, were told to practice a mental “loving kindness meditation” thought to elicit compassion. When they did this, it suppressed that empathy for pain network.

Singer took this research a step further and asked another monk, Matthieu Ricard, formerly a molecular biologist, to empathize with the women’s suffering instead of practicing the compassion meditation. His empathy for pain network went gangbusters, and he asked her to stop the experiment almost as soon as it began, calling the sensation “unbearable.”

Ricard said, “Compassion is feeling for and not with the other.”

Singer finds the distinction very important. “…These studies have also shown that it is crucial to distinguish between empathy, which is in itself not necessarily a good thing, and compassion,” Singersaid in an interview with the Cognitive Neuroscience Society. “When I empathize with the suffering of others, I feel the pain of others; I am suffering myself. This can become so intense that it produces empathic distress in me and in the long run could lead to burnout and withdrawal. In contrast, if we feel compassion for someone else’s suffering, we do not necessarily feel with their pain but we feel concern – a feeling of love and warmth – and we can develop a strong motivation to help the other.”

There are other unexpected downsides to empathy: Michael Poulin, an associate professor of psychology at the State University of New York at Buffalo published research last year suggesting that empathy can also lead to aggression, particularly when a person witnesses someone they care about being mistreated. “Experiencing a suffering person’s distress as if it were your own is highly aversive and unpleasant,”he said.

Perhaps the most vociferous critic of empathy is Yale psychologist Paul Bloom, who wrote a book titled Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion. He feels that by empathizing with one person or group, we actually limit our ability to make rational or fair decisions for the greater good.

In his book, he gives an example of a University of Kansas study from 1995. Study lead, psychologist C. Daniel Batson, told participants about a charity called the Quality Life Foundation, whose main aim was to improve the quality of life for terminally ill kids. They were told they would hear an interview with a child applicant. (Yes, the charity and the terminally ill child were both fake).

They created two study conditions. “Low-empathy” and “high-empathy.” For the high-empathy condition, participants were asked to really imagine what the child had been through, to identify with the child’s feelings and experiences to get the full impact. In the low-empathy condition, they were guided in the opposite direction: to not be drawn into feelings but stay objective and detached in order to really hear the child’s story.

After listening to the allegedly terminally ill child, “Sheri Summers,” volunteers had to make a tough decision: would they move Sheri up on the charity’s wait list, bumping out other terminally ill kids who would then have to wait longer?

“The effect was strong,” Bloom wrote in his book, “Three-quarters of the subjects in the high-empathy condition wanted to move her up, as compared to one-third in the low-empathy condition. Empathy’s effects, then, weren’t in the direction of increasing an interest in justice. Rather, they increased special concern for the target of the empathy, despite the cost to others.”

Bloom calls this process of zooming in on one person’s pain at the expense of others the “spotlight effect.” A real life example of this, he explains, is when the Make-A-Wish Foundation spent quite a few thousand dollars to help a terminally ill child play Batman for a day. The counter argument is, that amount of money could have helped multiple children with slightly less dramatic displays of charity.

He promotes something called “rational compassion” instead. He defines compassion as “simply caring for people, wanting them to thrive.” From this standpoint, he argues that you don't have to get personally emotionally invested, and you’re more likely to keep your rational mind about you in the process.

Since beginning her studies on empathy and compassion, Singer, too, has shifted from empathy to compassion. She even created compassion trainings for people who are at greater risk of empathy burnout due to their jobs.

Compassion training redirects a person away from the “shared pain” of empathy and back toward the loving kindness meditations grounded in Eastern traditions, such as Buddhism or Hinduism. According toone study, which put the training to use, the training fostered “benevolent and friendly attitudes toward oneself and other persons…Ultimately, the goal was to develop compassion as a generalized prosocial feeling and motivation, independent of particular persons or situations.”

One of the participants of this training, Irina Schroen, a neonatal nurse at Charité University Clinic in Berlin, Germany, was about to quit her career due to compassion fatigue. She feels that Singer’s training saved her life and her career. “My colleagues are once again happy to work with me,” she said. “They say ‘It’s incredible how relaxed you are now.

The end result of all this study may be that empathy is good in small doses, but, as Poulinsaid, “It’s not at all clear the world needs more empathy if that means experiencing another person’s suffering as your own. Doing that may simply double the world’s suffering.”

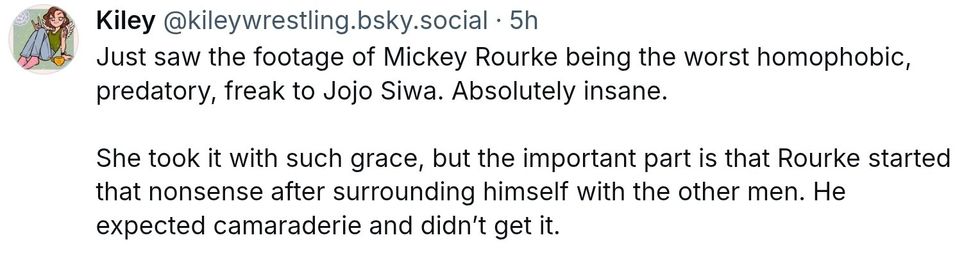

@kileywrestling/Bluesky

@kileywrestling/Bluesky