The most feared viruses are those for which medical science has not yet developed a treatment, cure or preventive vaccine. Often, such viral agents have only been recently discovered and emerged as an outbreak in a particular region of the world. This is the case for the Nipah virus (NiV), which has claimed the lives of at least nine people in India this year.

Nipah virus was first discovered in Malaysia in the late 1990s when an outbreak of the virus struck approximately 265 people. People became sick after physically interacting with pigs in the area, with symptoms manifesting as brain inflammation.

Of the 265 that contracted the disease, 105 lost their lives. The fatality rate jumped from 40% to 75% with subsequent outbreaks, which took place in Bangladesh and India. Authorities followed established protocols for containing the zoonotic disease, a contagion spread from animals to humans, through the culling of the apparent host species: pigs.

The impact of these actions was moderate as it was determined that NiV could not only transmit from pigs to humans, but also that person-to-person transmission was possible.

Later investigations identified two species of sizable fruit bats also known as “large flying foxes” and “small flying foxes” as the natural host reservoirs for the Nipah virus.

The course of infection in humans begins with disorientation, drowsiness and headaches, which progresses to influenza-like symptoms including: general weakness, fever, nausea, vomiting, pain in the abdomen, followed by eventual encephalitis. The most severe cases see a combination of acute encephalitis and seizures. Despite the absence of any medical treatments for the disease, people can survive infection with NiV, though they are often left with neurological disorders marked by aberrations in personality and recurrent seizures.

During the preparation of this article, health officials in India declared that the “highly dangerous phase” of the recent 2018 NiV outbreak was over. This conclusion was reached after no new cases of human infection were reported in more than two weeks after the initial flare-up of the disease in India. By this point, a “second phase” of new NiV infections were anticipated based on previous outbreaks, but this has not transpired. The number of cases had advanced to 18 of which 16 of the patients had died due to NiV. The two remaining NiV-infected individuals were responding well to treatment with Ribavirin, a potent anti-viral drug. Both were reported to be virus-free, though a decision has yet to be reached on when to discharge them.

Beyond this current, apparently contained, NiV outbreak in India, should there be greater global concern about this virus? Both the United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) have classified NiV as a pathogen that has the potential to become a pandemic agent. A pathogen that can cause a pandemic is one that has a high level of communicability among people to spread across the globe in a relatively short amount of time. For example, it took just months for the H1N1 influenza epidemic of 2009 to reach pandemic status. Fortunately, in that instance, the lethality of the virus was less than what was anticipated.

In light of the recent NiV outbreak, a virus that the WHO ranks in its top priorities alongside Ebola virus and Zika virus, a global health consortium called the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (or CEPI) awarded 25 million dollars to biotech companies in the United States that have been leading the charge to develop a NiV vaccine.

There are at least two different experimental NiV vaccines that have shown protective results when tested in animal models. One vaccine candidate involves a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) decorated with the immunogenic glycoprotein of NiV. VSV is a well-studied virus that has been attenuated in the laboratory setting and has been investigated for its capacity to be genetically altered to have its surface coated with immune system stimulating molecules from a variety of different viruses. The VSV-NiV vaccine offered protection from NiV infection in African Green Monkeys after a single-dose.

A virus-like particle (VLP) derived from the actual Nipah virus is the basis of another vaccine candidate. Scientists were able to produce a VLP that was structurally similar the natural virus but was composed of only three of the NiV proteins. These proteins self-assembled into a virus particle that should be as immunogenic as NiV. This approach has advantages for when it comes time for regulatory agencies to approve its use on humans, since the VLP lacks the biological components necessary for replication and therefore is incapable of mutating and producing new virus when administered to a person. When tested in hamsters, both single-dose and triple-dose regimens offered complete protection against NiV.).

Finally, there is one possible therapeutic approach to treating individuals already infected with NiV. A special antibody has been developed by scientists at the University of Queensland in Australia. The antibody, called M-102.4, has yet to be patented and has not been clinically tested in humans. However, in the laboratory, M-102.4 has proven effective in neutralizing NiV in infected cells. The antibody has been shipped to India as a possible treatment for NiV-infected individuals should the current outbreak flare up again or in the event of the emergence of NiV in another region.

The recent developments of the aforementioned vaccine platforms and the antibody therapeutic offer some hope in the battle against Nipah virus around the globe. However, until there is a vaccine, a cure and treatments that have been clinically tested and verified in humans, detection and containment procedures will be the best defense against this virus that has the potential to spread worldwide.

i know right schitts creek GIF by CBC

i know right schitts creek GIF by CBC  nurse ward GIF

nurse ward GIF  Organ Donation Kidney GIF by I Heart Guts

Organ Donation Kidney GIF by I Heart Guts  Hell Yeah Deal With It GIF

Hell Yeah Deal With It GIF

@latoyajackson/Instagram

@latoyajackson/Instagram @latoyajackson/Instagram

@latoyajackson/Instagram @latoyajackson/Instagram

@latoyajackson/Instagram @latoyajackson/Instagram

@latoyajackson/Instagram @latoyajackson/Instagram

@latoyajackson/Instagram @latoyajackson/Instagram

@latoyajackson/Instagram @latoyajackson/Instagram

@latoyajackson/Instagram @latoyajackson/Instagram

@latoyajackson/Instagram @latoyajackson/Instagram

@latoyajackson/Instagram @latoyajackson/Instagram

@latoyajackson/Instagram

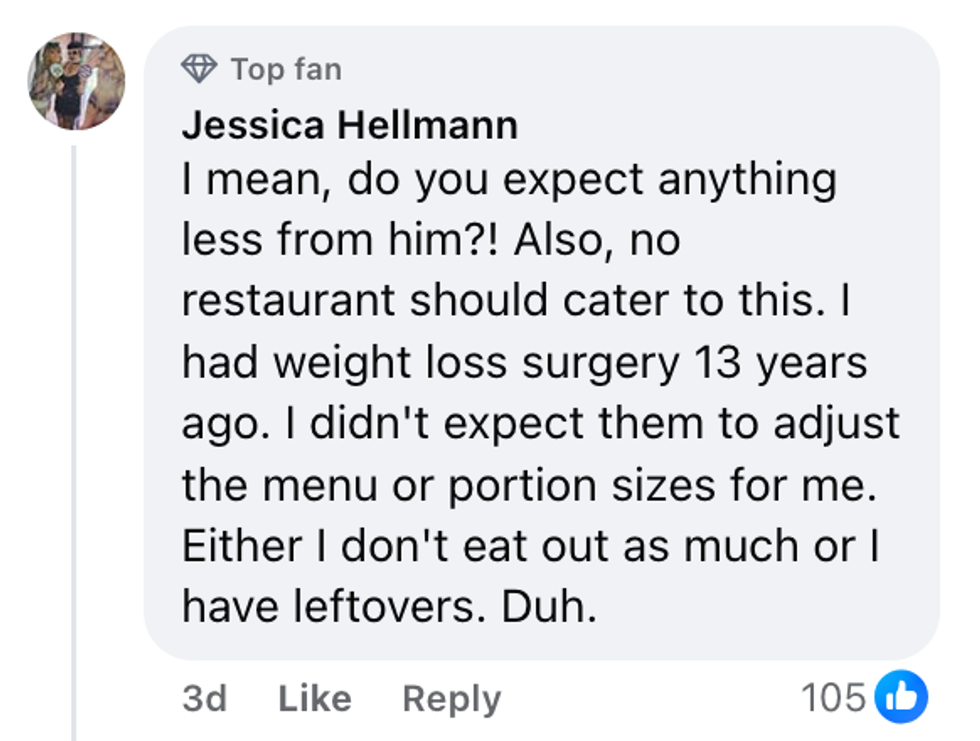

Jessica Hellman/Facebook

Jessica Hellman/Facebook Beatha Sellman/Facebook

Beatha Sellman/Facebook Medal Jeannette June/Facebook

Medal Jeannette June/Facebook Mellisa Wisser/Facebook

Mellisa Wisser/Facebook Stephanie Bertsch/Facebook

Stephanie Bertsch/Facebook Christina Borja McAlvey/Facebook

Christina Borja McAlvey/Facebook