You may think of scarlet fever as one of those Victorian illnesses, now thankfully eradicated with modern medicine, which afflicted the consumption-weakened people of the era. In fact, scarlet fever is the result of a common bacterial infection gone untreated. The culprit is Group A streptococcus, which typically resides on our faces and in our throats, and is responsible for scarlet fever, strep throat, and impetigo.

While the infection has been controlled through better hygiene practices and antibiotics, reducing its incidences, it’s been making a dramatic comeback in the past couple years, leaving scientists scrambling to understand why.

With concern for public safety, researchers at the National Infection Service and Public Health England recently published a study in The Lancet attempting to get to the root of this viral conundrum.

But first, an overview: back in the 19th century, scarlet fever ravaged England and Wales and even parts of the US, accounting for as many as 36,000 deaths, mostly children, from this illness you rarely hear much about today. And those who survived scarlet fever could also wind up with one of its many long-term side effects, which include rheumatic fever, an inflammatory disease that can affect the heart, joints, skin and brain; kidney disease; skin infections; pus-filled abscesses in the throat, pneumonia and arthritis.

Scarlet fever typically begins with a high fever and an uncommonly painful sore throat. If not caught, it may then progress to nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain. The signature sand-papery red rash across the face and/or torso which gives the illness its name may come in the early days of infection or as late as seven days into the illness, followed by bright red skin in underarm, groin and elbow creases. Your tongue can become inflamed and covered in whitish bumps, a condition known as “strawberry tongue” that can make eating uncomfortable.

The bacteria is contagious to others if they drink or eat from a cup or utensil used by the sick person, or if they come in contact with bodily fluids (through sneezing or coughing) or any open sores on the afflicted person’s body. However, all of the symptoms can be easily cured with a course of antibiotics, which is why scarlet fever is no longer considered a lethal illness.

According to the BBC, back in 2014, the UK saw a 50-year high of the bacterial infection with over 19,000 cases from 620 outbreaks reported in 2016, most commonly in schools and nurseries, though it strikes adults, too. This is the highest number of reported cases since 1967, reported Science Alert, a significant boost from 2013, when there were just 4,643 reported cases and seven times higher than the reported numbers in 2011. That same year Hong Kong saw an exceptionally high uptick of scarlet fever cases, which led to several deaths. In fact, a health website called Passport Health said that some researchers believe the outbreak in Asia may have influenced its spread in the UK.

The rise of antibiotics after about 1945 markedly reduced the numbers of cases annually, which is why these resurgences in the UK, as well as in parts of South Korea, Vietnam, China, and Hong Kong are stumping disease specialists who can’t put their fingers on a specific cause.

In an attempt to find a root of the recent increase in infections, The Lancet study authors, led by epidemiologist Theresa Lamagni of Public Health England, looked at bacterial samples from 303 infected patients in 2014.

The first most obvious theory was that antibiotic-resistant new strains of the bacteria have proliferated. However, at least in the UK study, the authors write that the strains they collected from patients with the infection in the UK “were not newly emergent strains but represented established lineages within our population.”

Another hypothesis is that this resurgence is an unusually virulent return to a natural cyclical pattern of the disease.

“This pattern was evident up until the 1940s and declined in the 1960s, in tandem with the widespread introduction of antibiotics,” the authors write.

While the recent upsurge in cases could represent a return to epidemic cycles, their analysis suggests “that the increase by seven times between 2011 and 2016, the lowest and highest points in the current cycle, is of greater magnitude than epidemic increases in previous years.”

It doesn’t help that a person can have scarlet fever for up to a week before symptoms really begin to show, making the spread of the illness more likely.

"Whilst current rates are nowhere near those seen in the early 1900s, the magnitude of the recent upsurge is greater than any documented in the last century," said Lamagni who led The Lancet study.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) does not track cases of scarlet fever so it’s difficult to know if there have been spikes here, as well, but according to STAT News, “Scientists there are aware of the spike in cases in some jurisdictions, but a spokeswoman said officials have not heard of an increase in the United States.”

In lieu of answers, scientists merely have hypotheses. Another one, according to Vox, is that it’s not the bacteria that’s changed, but something in the immune systems of people that has changed or is being affected, which has caused them to be more susceptible to the Streptococcus pyogenes bacterium. Perhaps some environmental factor.

In an attached editorial along with The Lancet study, Professor Mark Walker from the University of Queensland in Australia wrote, "Group A Streptococci come in many different serotypes [variations]. Therefore, waning immunity against a particular serotype may open up the population to certain types of [strains] capable of causing scarlet fever."

Another theory is that people coming down with scarlet fever now may be “co-infected” with another as of yet unidentified pathogen that predisposes them to the infection or weakens their immune system, allowing the strep to proliferate.

Most of the cases of scarlet fever were not severe, and there were no reported deaths in the UK (though there were a couple in Asia), but there was a higher than usual rate of hospital admission, and, the authors write, “the impact on public health has been substantial, particularly with regards to the management of the outbreak.”

In the meantime, the authors of the study say they are concerned about the spread of the illness, but not overly alarmed. The best defense to any pathogen is good hand washing practices. And if you or someone you know develops symptoms, get to a doctor sooner than later, and antibiotics will nip it in its scarlet bud.

@lamorne/Instagram

@lamorne/Instagram @bigbeaubrown/Instagram

@bigbeaubrown/Instagram @musiccitykristy/Instagram

@musiccitykristy/Instagram @phil_torres/Instagram

@phil_torres/Instagram @vbarreiro/Instagram

@vbarreiro/Instagram @franklinjleonard/Instagram

@franklinjleonard/Instagram @br1an02/Instagram

@br1an02/Instagram @ohhelloitsmax/Instagram

@ohhelloitsmax/Instagram @frecklesmarie/Instagram

@frecklesmarie/Instagram

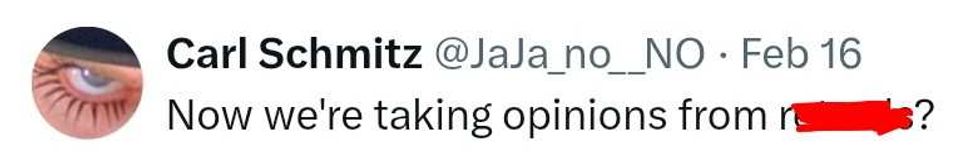

@JaJa_no_NO/X

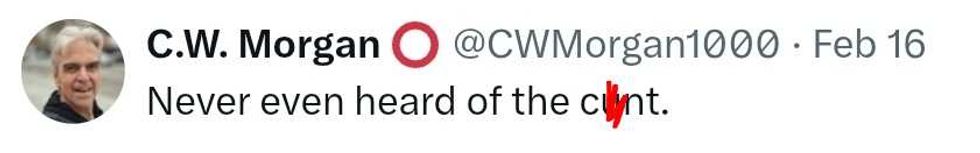

@JaJa_no_NO/X @CWMorgan1000/X

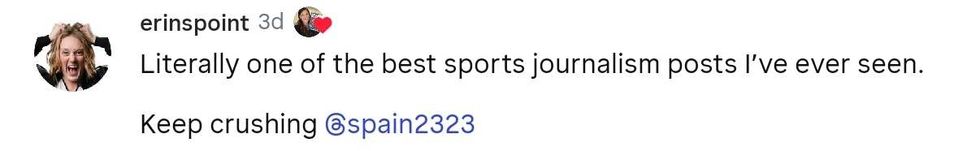

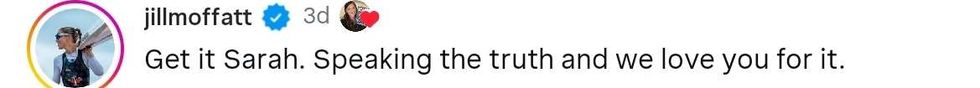

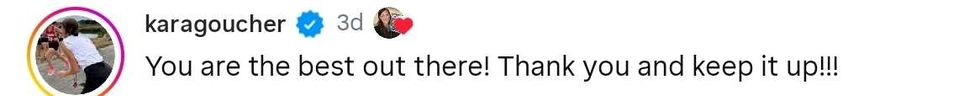

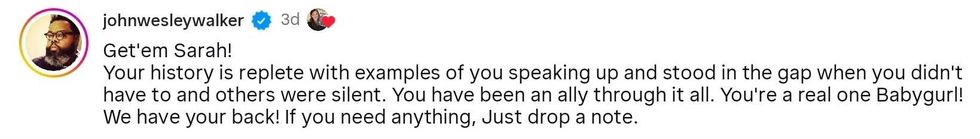

@CWMorgan1000/X reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram reply to @spain2323/Instagram

reply to @spain2323/Instagram