Once wilderness is gone, it’s gone for good. A new study published by the University of Queensland finds that Earth’s wildernesses are disappearing at a rapid rate, and emphasizes that once degraded, there’s no evidence to suggest they can be fully restored.

Led by UQ professor James Watson, also a director of science with Wildlife Conservation Society, researchers mapped global wilderness areas lost since 1992. They concluded that 10 percent of all wilderness areas had vanished in that time. “If this rate continues, we will have lost all wilderness within the next 50 years,” concluded Watson.

The team attributed declines to human activity, from mining and logging to farming and road-building. “It is death by a thousand cuts,” noted Ph.D. student James Allan, who assisted with the study. “The moment you put a road in, you get people moving in to farm, hunt, and [that] undermines the wilderness.”

“Wilderness” is a hard concept to pin down. According to the 1964 US Wilderness Act, wilderness is “an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character…[that] generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable.” Historically, this ambiguous definition has left many pristine areas vulnerable to policymakers’ varying interpretations.

The impact of wilderness degradation is far less ambiguous. In addition to housing countless threatened species, researchers say wilderness plays a vital role in processes as diverse as migration patterns, pollination, and nitrogen and water cycles.

It also serves as a front line against climate change’s increasing impacts. Said Watson: “Intact functioning ecosystems are critical not only for biodiversity but for the huge amounts of carbon they store and sequester. They provide a direct defence against climate-related hazards like storms, floods, fires and cyclones,” and their destruction has the potential to unleash massive amounts of carbon into the atmosphere.

Even development that leaves portions of wilderness untouched can have unforeseen consequences, rippling throughout an entire ecosystem: “The risk is that a lot of these systems could collapse. The Amazon is the best example of where you need the whole forest, or a huge portion of the forest, protected for the hydrological cycle to function.” The team’s map indicates that one-third of the Amazon wilderness has vanished since 1992.

Other particularly at-risk regions include much of Africa, the deserts of Central Australia, the Tibetan plateau in central Asia, and the boreal forests of Canada and Russia. Indigenous communities in these regions will face potentially grave ramifications: “You have got people living in the Amazon, Congo and New Guinea who have been there for thousands of years… So loss of wilderness will have huge ramifications for local people and their livelihoods.”

Conservationists continue to push back against policies that threaten the planet’s remaining pristine areas. This December, wilderness advocates pledged to fight President Trump’s authorization of oil drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, one of the nation’s largest remaining wilderness areas.

“You can have the oil. Or you can have this pristine place. You can’t have both. No compromise,” noted Robert Mrazek, former chair of the Alaska Wilderness League. The 1.5 million acre area at stake, known colloquially as “America’s Serengeti” due to its rich biodiversity, provides a home for polar bears and grizzlies, as well as a vital breeding ground for millions of migratory birds and about two hundred thousand caribou.

Large-scale development projects, such as China’s upcoming “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI), may affect wilderness areas on a global scale. The estimated $4 trillion project will cut massive swathes through remote lands and protected wildlife areas in its goal to connect 65 nations and half the planet’s population.

Environmental experts from the University of Nottingham Malaysia and the University of Nottingham Ningbo China recently challenged officials to place wilderness and biodiversity conservation at the heart of BRI. The team outlined BRI’s potential devastating threats to wild lands, and proposed its planners work hand-in-hand with conservationists to follow environmental best practices in carrying out the project.

Encoding wilderness protection into policy is easier said than done. The team admitted that enacting their plan would require buy-in from a host of different parties ranging from governments to developers to civil societies.

As it stands, rapid wilderness depletion seems unlikely to halt anytime soon. Still, studies such as the University of Queensland’s prove crucial in raising awareness of the situation’s gravity; after publishing the team’s findings, Watson reported receiving “multiple” requests from policymakers around the world, including the UN. Watson himself describes his findings as a call to action: “We have got to turn the corner, we have got to bend the curve, we have got to change this and save the last brilliant irreplaceable places.”

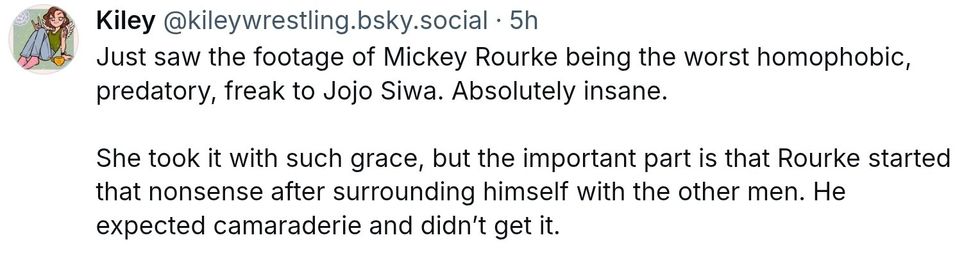

@kileywrestling/Bluesky

@kileywrestling/Bluesky