Earlier this year, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a study from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, which found 416 cases of advanced black lung disease in coal miners in central Appalachia from 2013 to 2017 — the highest cluster of cases ever seen. The institute also confirmed a 2016-2017 investigation by National Public Radio (NPR) that discovered hundreds of other cases in southwestern Virginia, southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky.

This research indicates that black lung is returning, even as safety measures have improved over the course of decades. Dust screens and ventilation had nearly removed the disease from the U.S. in the 1990s, but these recent studies suggest otherwise in coal country.

Take Barry Shrewsbury of West Virginia, for example: He worked in mining as a younger man, and presently, at age 62, has difficulty breathing and going about basic daily tasks, like showering and shopping. For his oxygen tank and medical care, Shrewsbury relies on a federal fund for miners with black lung disease, called The Black Lung Disability Trust Fund.

The fund is currently under threat of dissolution. Increasing debt and cuts to contributions from the coal industry scheduled for the end of 2018 put it at risk of insolvency, according to two sources from the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) in an interview with Reuters.

With black lung hitting rates unseen in decades, this is particularly dangerous as this could shift some of the financial burden to taxpayers, potentially slashing the benefits for recipients. The fund has already reluctantly borrowed more than $6.5 billion from the U.S. Treasury to finance the program, according to the Treasury Department. About half of the fund's revenue is currently allocated toward repayment of that debt.

Kirsten Almberg, an assistant professor of environmental and occupational health at the University of Illinois at Chicago, who wrote a grim analysis of Labor Department data, remarks, “This is history moving in the wrong direction.” Her analysis revealed that almost half the 4,679 benefits claims from miners with the most treacherous form of black lung were made in the years since 2000.

Former miners and health professionals in the region believe the resurgence of the disease is due to longer hours in deeper reaches of the old mines, in addition to slack safety measures and newer machines that can now puncture through layers of rock.

Presently, the fund covers medical expenses and monthly living expense payments for over 15,000 people, according to a Congressional report published this year. It also pays benefits to miners severely disabled by black lung in cases where no applicable coal company can directly provide support, like when a company bankrupts, which is fairly common given the advent of wind and solar power. About 2,600 medical claims were taken from companies and given to the fund in 2017 due to bankruptcies, according to a 2018 Congressional report.

Yet, the coal industry is lobbying Congress to promote the scheduled tax reduction under the belief that that payments are too high for mining companies and the fund has seen abuse from undeserving applicants.

Medical experts describe the disease as an incurable illness caused by the inhalation of coal dust, and explain that it is easy to distinguish from other diseases, using x-rays. Dr. David Blackley of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, an offshoot of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), asserts that “it is not caused by smoking.”

Bruce Watzman, head of regulatory affairs for the National Mining Association, believes the fund is subsidizing previous or current smokers. He bases his view on “discussions with those administering this program for companies,” though he, himself, has performed no research on the misallocation of benefits. He later cited a study from 1989 by the University of Louisville School of Medicine, which examined 1,000 black-lung benefit applications and found that coal miners judged “potentially eligible” for benefits smoked at higher rates than those who did not qualify.

Jim Werth, the black lung clinic director at Stone Mountain Health Services in St. Charles, Virginia, disagrees with the assertions that the fund is covering applicants who do not technically qualify or are otherwise ineligible. He claims the process in itself makes qualification difficult, especially with barriers like coal companies hiring physicians to challenge medical test results. In the meantime, many of these individuals are unable to work and paralyzed by medical expenses.

To qualify for benefits, a miner must first apply to the Department of Labor. Next, the application is screened based on medical and employment documentation. The Department of Labor then attempts to find a responsible coal company to fund the costs, and in doing so must consider all potential causes of an applicant’s lung problems prior to awarding benefits. This yields an approval rate of about 20 percent, or at least was the case in 2017.

Coal companies are taxed $1.10 per ton on underground coal production to finance the fund, but the tax will revert to the 1977 level of $.50 by the conclusion of 2018 if Congress does not extend the current rate.

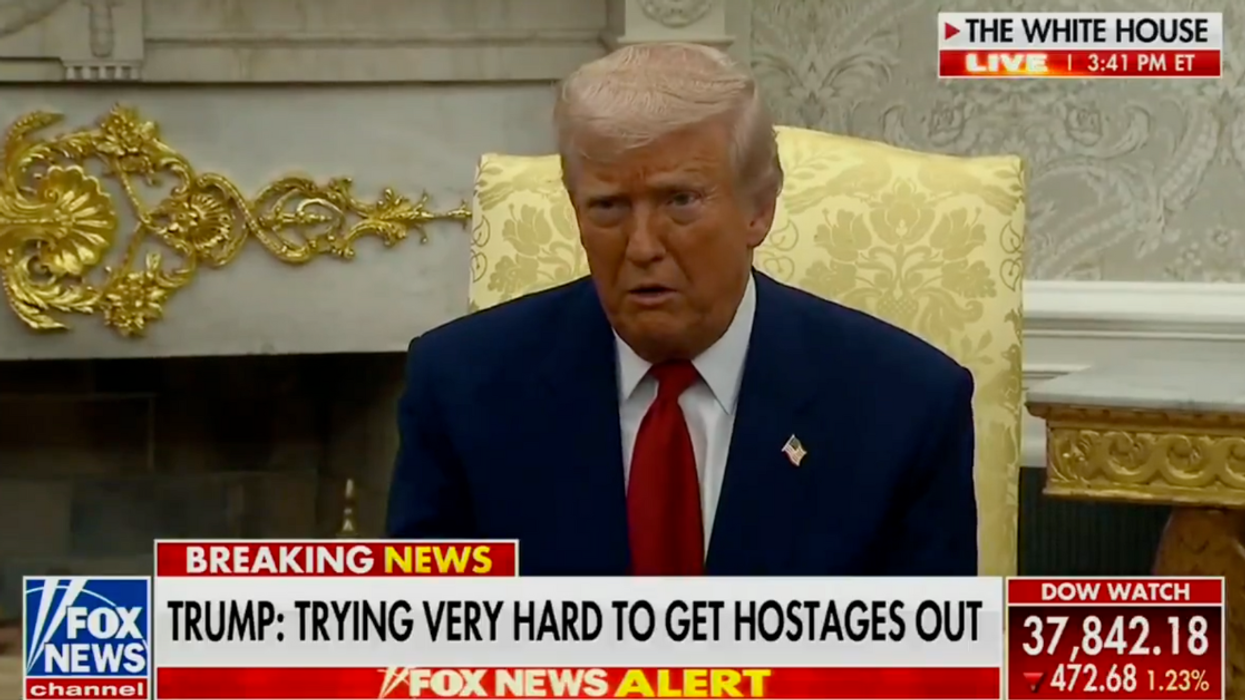

An extension of the current excise coal tax failed earlier this year after the National Mining Association lobbied Republican House leadership against it, though discussion will likely return following the release of the GAO report, which was requested back in 2016 by Democratic Congresspeople Bobby Scott (D-VA) and Sander Levin (D-MI). It has undergone review by the Trump administration, who have focused on deregulating the coal industry.

For recipients like Barry Shrewsbury, “the benefits are a lifeline."

@jordeeeeeeee/TikTok

@jordeeeeeeee/TikTok @jordeeeeeeee/TikTok

@jordeeeeeeee/TikTok @jordeeeeeeee/TikTok

@jordeeeeeeee/TikTok @jordeeeeeeee/TikTok

@jordeeeeeeee/TikTok @jordeeeeeeee/TikTok

@jordeeeeeeee/TikTok @jordeeeeeeee/TikTok

@jordeeeeeeee/TikTok @jordeeeeeeee/TikTok

@jordeeeeeeee/TikTok @jordeeeeeeee/TikTok

@jordeeeeeeee/TikTok @jordeeeeeeee/TikTok

@jordeeeeeeee/TikTok @jordeeeeeeee/TikTok

@jordeeeeeeee/TikTok