Overburdened healthcare systems, as they attempt to weather the storm of unsustainable inflows of patients, have been forced to adopt daily, desperate changes to rules and regulations over the last month.

The results are very public, high-stakes adaptations to new problems.

For the New York State Health Department in the midst of the pandemic, less than a day is needed for a brutal decision to be mulled over in private, publicly declared, face mountains of backlash and be scrapped altogether in the end.

That was the case with a do-not-resuscitate order given on the afternoon of April 20.

Less than 12 hours later, just before noon on April 21, the New York Posthas reported that on-scene resuscitation is authorized again in New York. According to the first report, also from the New York Post, New York state, though finally seeing decreasing daily numbers of new cases, hospitalizations, is not out of the weeds yet.

The daily death toll is still on the rise. as those confirmed to have the virus drop daily, the treatment or worsening symptoms of those previously diagnosed comes into play. This leads to shortages in ICU beds and ventilators and equipment needed to monitor patients vital signs.

That means hospitals remain overburdened and unable to keep up with the current number of patients.

In response, the state's Health Department decided Wednesday to adopt standard emergency disaster medical triage protocols. Such triage tells paramedics to not resuscitate people when no heartbeat is detected as there may be no way to keep the patient alive once they reach the hospital.

Previously, the state directed first responders to spend up to 20 minutes attempting to revive a stopped pulse at the scene. The new guidance, according to a memo from the Health Department, instructs spending no time on these efforts.

The memo, according to New York Post, gave the following rationale:

"[These measures are] necessary during the [virus] response to protect the health and safety of EMS providers by limiting their exposure, conserve resources, and ensure optimal use of equipment to save the greatest number of lives.''

While those trained in disaster preparedness recognize the guidance as standard procedure, the directive was met with broad public opposition from a range of voices.

Oren Barzilay, the head of a union that represents first responders in NYC, was staunchly against the measure.

"They're not giving people a second chance to live anymore. Our job is to bring patients back to life. This guideline takes that away from us."

One veteran FDNY worker laid it out even more bluntly to the New York Post:

"Now you don't get 20 minutes of CPR if you have no rhythm. They simply let you die."

Though less than a day after the guidance was given and the outrage spewed, the Health Department bowed to public pressure and rescinded the directive.

In a statement, the department cited its reasons for making the original decision, noting the guidance was in line with the recommendations of "physician leaders of the EMS Regional Medical Control Systems and the State Advisory Council," the American Heart Association and "based on standards recommended by the American College of Emergency Physicians."

The statement then highlighted New York's higher standards, as voiced by the outraged first responders of the prior day:

"However, they don't reflect New York's standards and for that reason DOH Commissioner Dr. Howard Zucker has ordered them to be rescinded."

The light speed back-and-forth did not go unnoticed on Twitter and Facebook.

During this public health crisis—with all levels of government scrambling to respond to such a massive struggle unseen in our lifetimes—one doesn't need to look far to find similar moments of quick decision-making as it happens in real time, right before one's eyes.

And while New York was able to reverse the guidance, some states may face the same dilemma soon as the virus spreads and some states choose to end containment measures before testing or a vaccine is available. More states may face the moral question of is it better to allow anyone with a stopped heart to remain as they are or to revive them only to watch them die at the hospital where the equipment needed to keep them alive is not available.

Hopefully, that does not come to pass.

The book Five Days at Memorial: Life and Death in a Storm-Ravaged Hospital, available here, explores the healthcare rationing at one New Orleans hospital after Hurricane Katrina where the patients outnumbered the resources to keep them all alive.

@PreetBharara/X

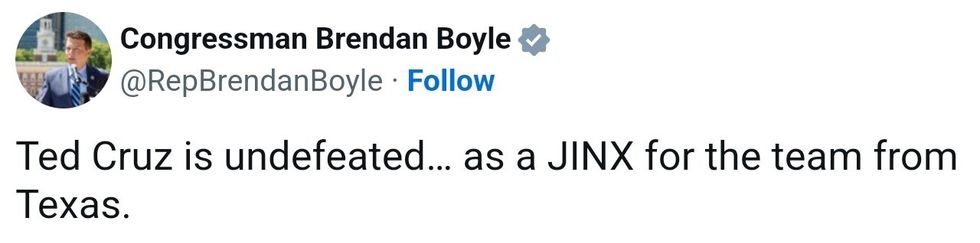

@PreetBharara/X @RepBrendanBoyle/X

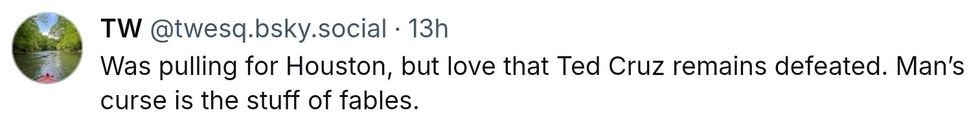

@RepBrendanBoyle/X @twesq/Bluesky

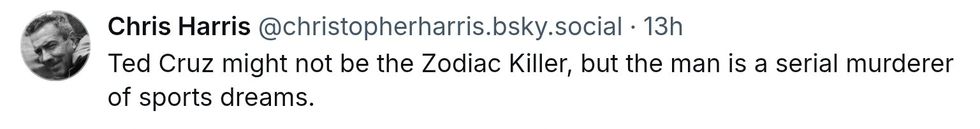

@twesq/Bluesky @christopherharris/Bluesky

@christopherharris/Bluesky @evangelinewarren/X

@evangelinewarren/X

@FrankC164/X

@FrankC164/X

AMC

AMC