They’re still counting ballots out in Arizona and California, and the path to 218 seats seems both tantalizingly close and ever-so-far, with two races in Arizona and three in California that we’d need to win looking like they’re going rather south on us.

Whether we wind up at 221/214 or 223/212, I should first make clear it is already a significant achievement to lose so few seats.

Historically speaking, in terms of House seats lost in a midterm, it’s looking like the best performance by a Democratic president since Bill Clinton’s second term in 1998 and the best by a new Democratic president since John Kennedy in 1962.

Still, when we’re this close, it’s worth asking why we couldn’t quite get to the finish line.

One answer I take a close look at today might make you a bit angry, so take a deep breath as we dive into some ugly history and even uglier realities.

Racial Gerrymandering, with a Nod from SCOTUS, Stole Three House Seats

Every 10 years, the census comes out and we go through a painful and time-consuming process called “redistricting”—meaning new Congressional and state district maps for each of the 50 states that has more than one House member.

Before the Civil Rights Era, this process was used by white politicians to lock minority voters out of political power by packing them together or cracking their neighborhoods apart.

If you want a great graphic on how this works, here’s one:

Racial gerrymandering to dilute minority representation continued unchecked until the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 protected more proportional representation through legal oversight and a “pre-clearance requirement” for new proposed maps requiring certain jurisdictions to submit their proposed maps ahead of time to the Department of Justice or the federal courts.

The Supreme Court gutted those protections in the 2013 Shelby County case, which found the system that identified which jurisdictions were covered by pre-clearance to be unconstitutional. It ordered Congress to come up with a new system that would pass legal muster.

Republicans, however, have been blocking those very efforts in the Senate through the filibuster, most recently by preventing a vote on the John Lewis Voting Rights Restoration Act.

Southern states, which were notorious before the VRA for locking out Black voters, went to work in 2021. In Alabama, Georgia and Louisiana, they drew maps that reduced African American representation by one seat in each state for a total of three formerly Democratic House seats.

Voting and civil rights groups sued.

Alabama was ordered to draw a map with two majority-Black districts out of seven total to ensure that Black voters—who make up one-third of the state’s population—are properly represented. In June of 2022, a Louisiana federal judge ordered new maps drawn holding that the proposed maps violated the VRA and that the proper remedy is a “remedial congressional redistricting plan that adds another majority-Black congressional district.”

But SCOTUS, in another of its infamous, unsigned “shadow docket” opinions, let the racially gerrymandered Alabama map stand during thiselection while the matter is being resolved in the courts. (Many legal observers say this was because SCOTUS plans to strike down all of the Voting Rights Act Section 2 protections as unconstitutional.)

It deployed reasoning from the newly concocted Purcell doctrine, which basically says that judges should not order changes in election procedures too close to an actual election. Later, it took the same action with respect to Louisiana’s maps, hitting pause on drawing up new maps to fix the racially discriminatory ones.

The problem, of course, is that by the time the first maps come out and racial minorities even get a chance to sue, the first post-redistricting midterm elections are upon us, and per Percell it’s now too late to change things.

This sets up a truly perverse incentive for state legislatures to draw the worst maps they can and run out the clock, then hope that any ruling against them gets stayed by SCOTUS because it’s now too close to the election to change things.

In her dissent, Justice Elena Kagan observed that the use of “it’s an election” year is a pretense for doing nothing. “Alabama is not entitled to keep violating Black Alabamians’ voting rights just because the court’s order came down in the first month of an election year,” she wrote.

GOP Governor Brian Kemp of Georgia understood the assignment. He waited a whole 40 days to sign new maps into law, putting the squeeze on voting rights groups by leaving them with little time to sue.

It worked as designed: A federal judge in Georgia, following SCOTUS’s lead, decided not to order a new congressional map for that state three months before primary elections, even though he agreed that the map, like Alabama’s, probably violated the Voting Rights Act.

Partisan Gerrymanders Skewed results in OH and FL

If you’re not feeling frustrated enough, there’s more.

The Ohio legislature’s maps were drawn up by its Redistricting Commission, which was dominated by Republicans. The Ohio Supreme Court ruled that their maps were unconstitutional under a new Ohio anti-gerrymandering amendment, but the Commission dragged its feet and risked contempt charges to keep the maps from being used, waiting seven weeks to produce a second map.

After a series of successive defeats before the state Supreme Court, the Republicans ran out the clock once again. Despite a ruling in July 2022 from the Ohio Supreme Court striking down the latest map, the state was officially out of time, and the highly skewed map was used in the November general election.

The map remained heavily weighted toward the Republicans, granting Democrats an outside chance to win only five of the state’s 15 congressional seats. Democrats in fact won all five, in a surprisingly strong showing.

The statewide senate race, however, showed a partisan split of 53/47, a far cry from the 66/34 House results that were set-up in advance through gerrymandering. Under a fair, constitutional map, Democrats might have won six or even seven seats given their performance.

In Florida, an already outrageously gerrymandered map, drawn up by the GOP-dominated legislature, was not enough for Ron DeSantis. He claimed (wrongly, it should be noted, under current law) that the maps unconstitutionally used race to draw district lines.

He therefore submitted his own maps which gave the GOP an even more lopsided likely result of 20 seats to the Democrats’ eight. The State Supreme Court declined to get involved, and in any event, once again the state was out of time to resolve the question before the general election.

Sure enough, the final results were 20/8 in favor of the Republicans in a state that is only generally slightly red statewide. (Prior to the redistricting, the old map had five competitive House swing districts, and in the new map it only has two.)

It’s a common saying that in a fair and free election, the voters pick their representatives, but in America’s gerrymandered states, the representatives pick their voters. That remains abundantly clear in Ohio and Florida.

Democrats Have Handed Redistricting Over to Independent Commissions and Courts

If this all feels very unfair, the final kicker is that in big blue states like California, New York, Michigan and Colorado, an independent commission draws up the redistricting plans, creating far better and fairer maps.

This year, New York actually tried to override that map using its supermajority in the legislature and lock in big partisan gains, but it got shut down by the New York state courts, contributing in part to the delegation’s poor showing, especially in key House races in the Hudson Valley and Long Island.

Had Democrats had the power to draw their own maps, or played dirty the way Ohio and Florida did, the House majority would be far more within reach.

The answer to all this is not an easy one.

Ultimately, we need some kind of national standard—like what was proposed in the Freedom to Vote Act—that would outlaw partisan gerrymandering even while protecting the representational interests of racial minorities.

To get there, we need to make some important structural changes to things like the filibuster rule, but we must do so when have control of both chambers of Congress and the White House and enough votes in the Senate to kill or weaken the filibuster.

That doesn’t look like it will happen in 2023-24 (we are one vote shy in the Senate even if we win the Georgia run-off and likely will not hold the House), but we can learn from these painful lessons and build toward a trifecta in D.C. come January of 2025. The power of that trifecta also has to be big enough to threaten to expand or otherwise reform the Supreme Court so that it discontinues its partisan shenanigans.

This is a lot to ask for and strive to achieve.

But at least we know the magnitude and the challenge of the task ahead.

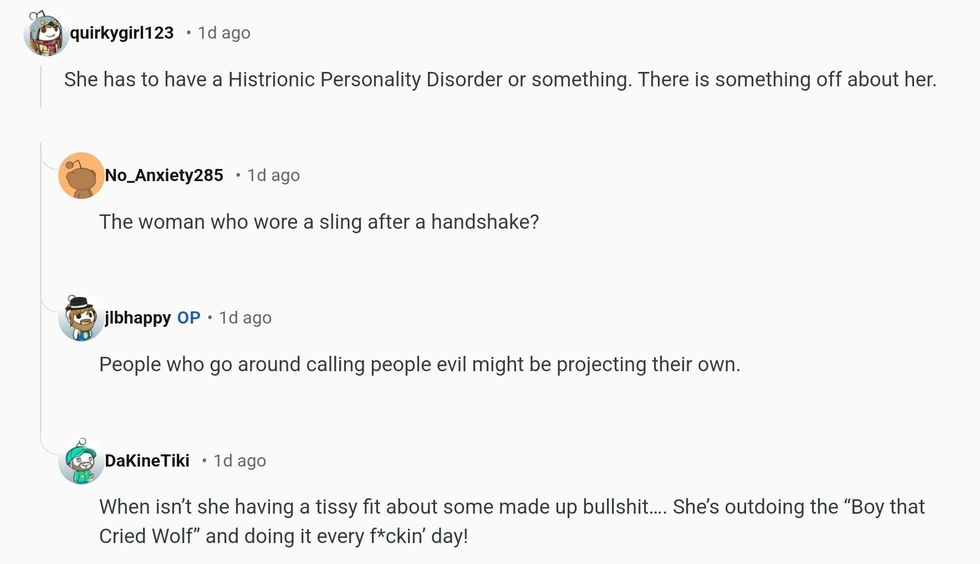

rPolitics/Reddit

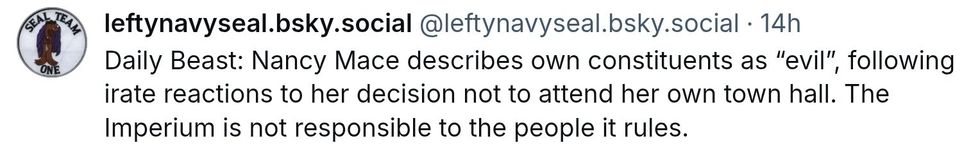

rPolitics/Reddit @leftynavyseal/Bluesky

@leftynavyseal/Bluesky rPolitics/Reddit

rPolitics/Reddit @skippyoz/Bluesky

@skippyoz/Bluesky rPolitics/Reddit

rPolitics/Reddit rPolitics/Reddit

rPolitics/Reddit rPolitics/Reddit

rPolitics/Reddit

jordi baste robot GIF by No pot ser! TV3

jordi baste robot GIF by No pot ser! TV3 sing schitts creek GIF by CBC

sing schitts creek GIF by CBC Well Done Ok GIF by funk

Well Done Ok GIF by funk Two Face Ernst GIF by ZWEIMANN

Two Face Ernst GIF by ZWEIMANN