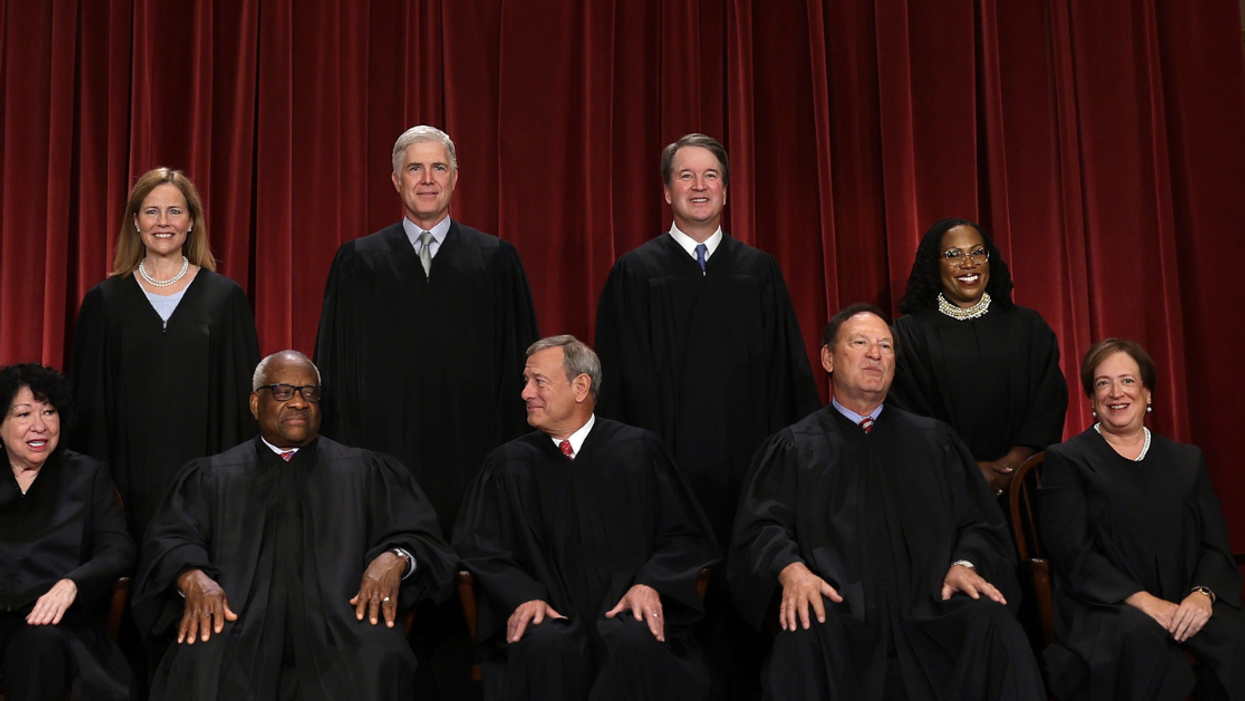

Yesterday, the Supreme Court heard arguments in one of the most anticipated— and dreaded—cases before it this term.

Moore v. Harper put what’s known as the “Independent State Legislature” (ISL) theory squarely before the nine justices, and that had a lot of legal scholars, civil rights advocates, and even a national group of state supreme court justices very nervous.

Just what is the ISL, and why is it considered so dangerous? And with this conservative SCOTUS, what are the chances it could inflict real and potentially catastrophic damage to our system of government?

Let’s helicopter over this new legal terrain and make some general assessments.

Background on the Case

Moore v. Harper is fundamentally a case about gerrymandering and who is allowed to stop its worst excesses. But because of the unique and frankly odd legal argument propelling it, Moore is also a bigger case about what power of state courts have to strike down or shape state laws around how federal elections are handled.

In 2021, the North Carolina legislature, which is dominated by Republicans, rammed through an extreme map of the Congressional districts for the state in a highly partisan gerrymander. North Carolina has 14 House Seats and is fairly evenly divided blue versus red in its state-wide votes. But the map would have basically guaranteed the GOP 10 out of the 14 seats.

Voters sued in state court under, among other things, the “free elections” clause of the state constitution. The North Carolina Supreme Court struck down the map as an “egregious and intentional” gerrymander that gave a “greater voice to [Republican] voters than to any others.”

The state legislature then proposed a new map that was also highly gerrymandered, which led to an order for a special master to create a fair map for the 2022 elections. The new map was likely to produce a more even split for the House delegation in the midterms.

Two Republican legislators then asked the U.S. Supreme Court to step in and reinstate their gerrymandered map, arguing that the Independent State Legislature theory of the Election Clause barred state court review of their map. SCOTUS declined to act on an expedited basis before the midterms, but decided to hear the underlying case anyway, which it did yesterday.

What ISL’s Proponents Have Advanced and Why It’s So Dangerous

The plaintiffs, backed by far-right conservative advocates, argue that under the Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution, state legislatures retain exclusive power over federal redistricting and election rules, while state constitutions, state courts, governors, or voter-approved ballot measures have no power to check, balance or even review those laws.

If that sounds totally insane and you need to re-read that last paragraph, go ahead. This is actually the argument that SCOTUS took up yesterday.

ISL’s proponents rely principally on their own interpretation of the Elections Clause, which states simply:

“The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof, but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations…”

The ISL proponents argue that this wording grants the power over the management of elections for federal office solely to the “Legislatures” without any role for the state courts and state governors to play.

Critics argue that, with federal courts sidelined by the Supreme Court but state courts now actively striking down partisan gerrymanders, Republicans are looking for a loophole through which to drive a big political truck of an argument.

Adoption of the ISL would give state legislatures, many of which are dominated by Republican majorities, complete and final say not only over how to draw Congressional maps, but over all rules governing federal election in their states.

This could lead to the worst excesses in this area, including extreme partisan gerrymanders, limiting judicial review of voter suppression laws, and subversion of state election results.

In theory, if the ISL theory were adopted as law, state legislatures could even pass laws making themselves the final arbiters of how a state’s electors act in a presidential election, irrespective of who won the popular vote.

The Arguments Against ISL

There are a host of reasons that ISL is simply wrong.

But chief among them is that this simply isn’t how our state systems and constitutions work. No state in the union currently gives state legislatures the unfettered power to do anything without some kind of restraint.

ISL is fundamentally undemocratic because it flies in the face of our traditional notions of checks and balances, where the judicial and executive branches at the state level are able to rein in the excesses of state legislatures.

This is supported by the historical record at the time of the framing of the Constitution. James Madison was worried that state legislatures would be captured by factions and engage in activities to benefit themselves politically.

He and other founders were proud of the fact the states each had their own constitutions and that the legislatures of the states would be constrained by them.

Plaintiffs’ argument, by contrast rests heavily on a very likely fraudulent document that has been discredited for 100 years. The language plaintiffs cited from something called the Pinckney Plan was actually nowhere in that plan when it was presented to the Philadelphia convention, and the bogus document was later openly questioned by James Madison.

Plaintiffs nevertheless led with this argument and called it “crucial” to their argument.

The textual reading ISL proponents advance also makes no sense. The Elections Clause gives the power to a state’s “Legislature” to set the “times, places, and manner” of federal elections but that same clause also states that “Congress may at any time by Law make or alter” those rules.

Does this mean the “Congress” can change those rules without getting the president’s signature, or that federal courts can’t review those changes? Of course not.

Yet that’s what ISL’s supporters say the “Legislature” can do in its own state.

The only way to reconcile the language is to presume, as the founders clearly intended, that both a state’s Legislature and our national Congress would still have to abide by the normal rules around passing laws, meaning they’d need an executive’s signature and they’d have to withstand challenge before the courts.

Even more on point, the Supreme Court already decided 90 years ago in the case of Smiley v. Holm that state governors may veto state legislative enactments concerning federal elections.

If state governors have such power over state laws concerning the times, places and manner of elections for federal offices, then there is no conceivable reason or reading of the Elections Clause that state courts don’t have a similar traditional role and function.

How the Supreme Court Appears to View the Case

It’s a dangerous pastime to predict how Supreme Court justices will rule in any case. Often they offer questions during argument in order to address some of their own misgivings or the dissent’s arguments before ruling the other way. With that caveat, it’s fair to say that defenders of our state constitutional system breathed a bit easier after yesterday’s oral arguments for Moore.

Observers in particular watched the three “swing” justices—Kavanaugh, Barrett and Roberts—closely for any signs of how they viewed the plaintiffs’ arguments. (It is a sign of the times we are in that these three conservative justices are now considered the “swing” votes.)

Chief Justice Roberts leaned heavily upon and frequently cited Smiley as a weight against the ISL theory. If the Election Clause supposedly gave to state Legislatures the sole and exclusive power to set the time, place and manner of federal elections, then Smiley would have had to be wrongly decided.

The Court would have to overrule that case, which Roberts seemed disinclined to do. Justices Kavanaugh and Barrett expressed similar qualms.

With the three liberal justices dead set against ISL and the swing votes not warming to the plaintiffs’ extremist arguments, the theory isn’t likely to find five votes even before this conservative Court.

Only Justice Gorsuch seemed entirely at ease with the arguments by the plaintiffs. It didn’t hurt that several conservative heavyweights, including Peter Keisler, one of the four founders of the Federalist Society, and Judge J. Michael Luttig of the Fourth Circuit weighed in against ISL in an amicus brief.

Even if the Court rules against the Moore plaintiffs, the case holds a warning for the future. The fact that at least four justices were willing to take up and entertain the question of ISL at all, one that cuts to the very heart of how our democratic system functions, should concern all of us.

We must remain highly cognizant that the systematic dismantling of long held rights, laws and precedents by this Court is showing signs of acceleration, not moderation.

And that means we must bring to bear greater vigilance, public education and legal activism than ever before.

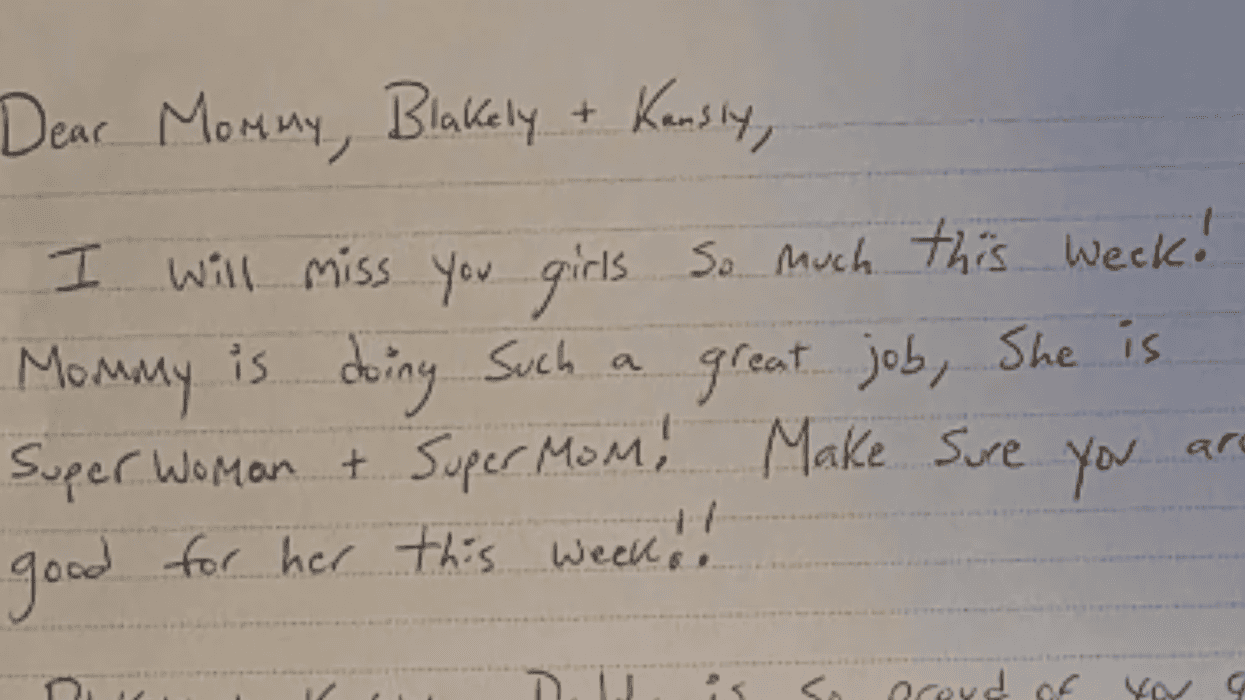

@jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram @jennifer.garner/Instagram

@jennifer.garner/Instagram

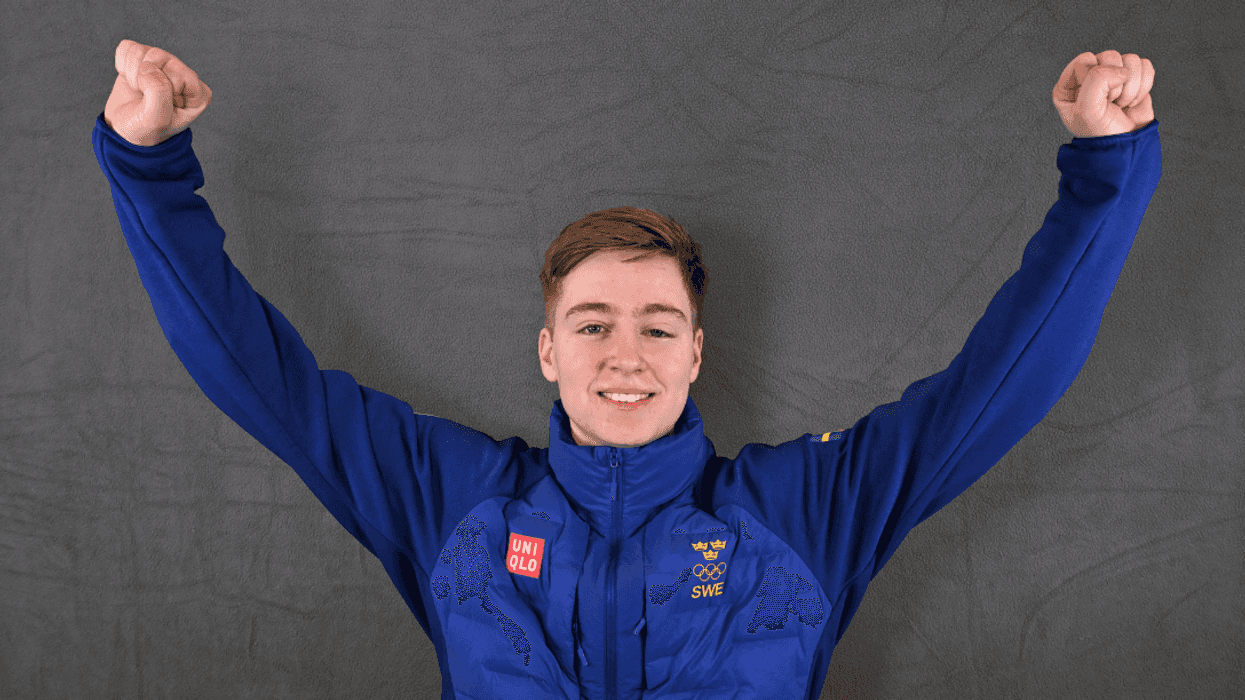

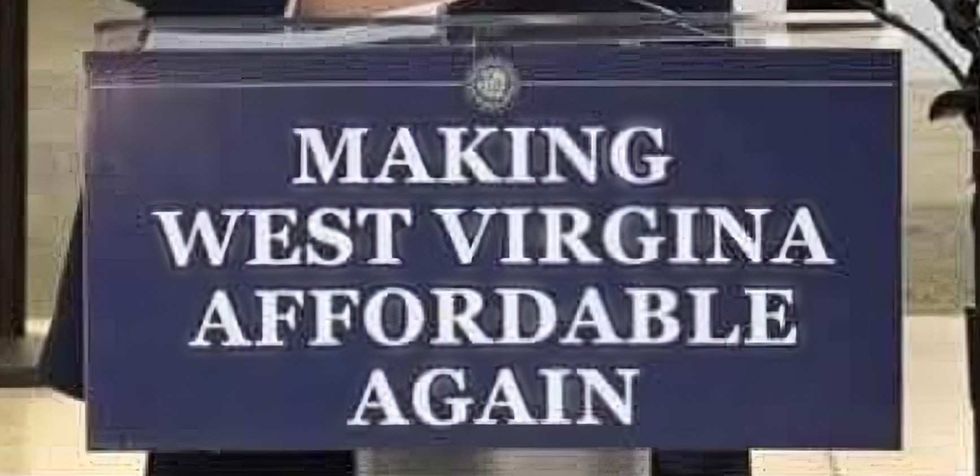

@ameliaknisely/X

@ameliaknisely/X WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit r/WestVirginia/Reddit

r/WestVirginia/Reddit WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook WDTV 5 News/Facebook

WDTV 5 News/Facebook