The appraisal for a Black woman's home in Indianapolis, Indiana increased by more than $100,000 after she restaged her home by removing Black identifiers like family portraits and African artwork.

Carlette Duffy, the homeowner, also had a White male friend present at the evaluation to give appraisers the impression the home belonged to a White person.

She has now filed a housing discrimination complaint in conjunction with the Fair Housing Center of Central Indiana (FHCCI).

Duffy seized an opportunity to refinance her home in a historically Black neighborhood just outside downtown Indianapolis. She was hoping to use the equity to purchase her grandparents' home nearby.

She purchased her house in 2017 for $100,000—and even though it was completely renovated after a fire—her first and second home valuations came back at $125,000 and $110,000, leaving her with very little equity.

So she was prompted to push back but to no avail.

She said:

"When I challenged it, it came back that the appraiser said they're not changing it."

Because her appraisals were estimated at a value close to the initial purchasing price of her home, she decided to conduct an experiment after hearing FHCCI Executive Director Amy Nelson talk to a community group about discrimination regarding home appraisals.

You can watch the news report, here:

Nelson referred to an article in TheNew York Timesduring the discussion that touched on the problematic tendency in the U.S. housing industry for a Black person's home to be appraised much lower than that of their White neighbor with a similar home.

This prompted Duffy to "do exactly what was done in the article."

Duffy said:

"I took down every photo of my family from my house. … I took every piece of ethnic artwork out, so any African artwork, I took it out. I displayed my degrees, I removed certain books."

Duffy reached out to a third lender for an appraisal, but this time, she did not disclose her gender or race on the application or in correspondence with the appraisal company.

She also had a White friend sit in on the valuation after informing appraisers she was going to be out of town and her brother would be there instead.

This time, the value of the third appraisal was estimated at $259,000.

Duffy had mixed emotions after receiving a higher appraised value of her home on the third attempt.

"I get choked up even thinking about it now because I was so excited and so happy, and then I was so angry that I had to go through all of that just to be treated fairly."

"Only when I removed myself did I increase the value. So I'm being seen as the object of devaluation in my home, and that part hurts."

"That's the part that's hard to get over."

In the two housing discrimination complaints, Duffy and FHCCI asked the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development to investigate the contrasting appraisals.

Nelson said the first two appraisals used comparable sales—or comps—taken from Black neighborhoods more than a mile away from Duffy's home instead of those nearby and similar to the style of her home to determine its value.

Said, Nelson:

"Whether or not those comps were fairly selected is something that is the basis of the complaints that we have filed."

She added:

"We think it's happening a lot more than is being reported and we want to get the word out to know that we are here as a resource for individuals if they feel this may be happening to them."

Duffy was able to use equity from the third appraisal to purchase her grandparents' house and keep it in the family.

She hopes her case will encourage a closer inspection into racial bias and discrimination in the housing industry and ensure protections for generations to come.

"I'm doing this for my daughter and I'm doing this for my granddaughter, so that when they come against obstacles they will know that you can stand up, you can say that this is not right."

@hebagowayed/Bluesky

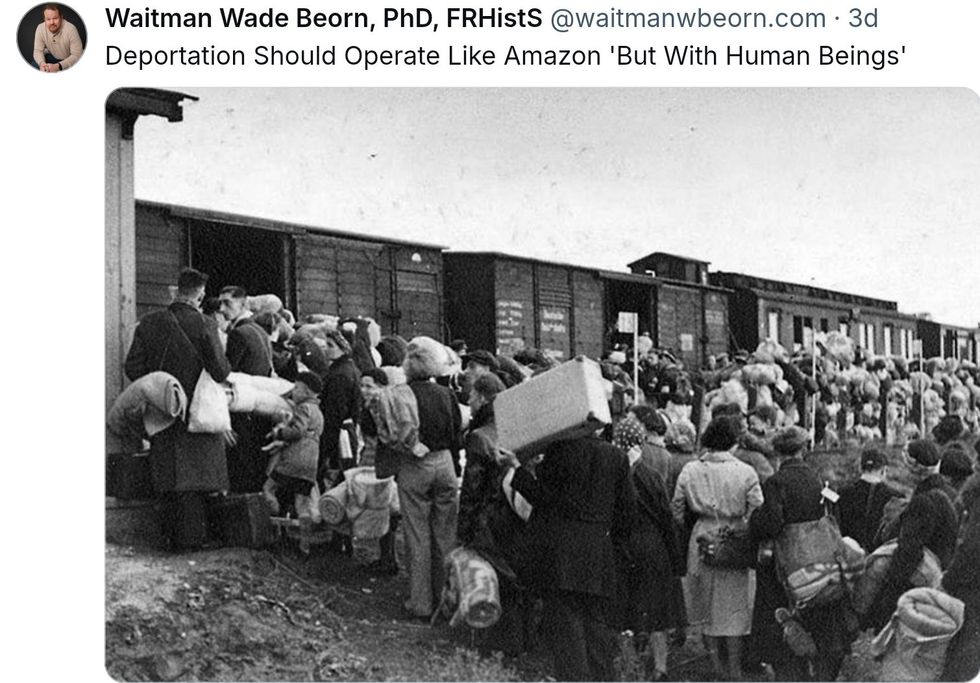

@hebagowayed/Bluesky @waitmanwbeorn/X

@waitmanwbeorn/X @eighthoften/Bluesky

@eighthoften/Bluesky  @antigonesdream/Bluesky

@antigonesdream/Bluesky

A1

A1