Insect apocalypse?

That's the phrase buzzing around the internet since the first global scientific review of insect population decline was published this week in the journal Biological Conservation.

Insects are superlative and have a crucial role in food webs and ecosystems. But they're dying out quite fast.

According to the study's authors:

"The pace of modern insect extinctions surpasses that of vertebrates by a large margin.

We estimate the current proportion of insect species in decline ... to be twice as high as that of vertebrates, and the pace of local species extinction ... eight times higher. It is evident that we are witnessing the largest [insect] extinction event on Earth since the late Permian and Cretaceous periods."

Overall, 40 percent of insect species on the planet are declining. Another third are considered endangered. The review's authors concluded that the total mass of insects worldwide is declining by 2.5 percent annually.

"It is very rapid. In 10 years you will have a quarter less, in 50 years only half left and in 100 years you will have none," study co-author Francisco Sánchez-Bayo, an environmental biologist at the University of Sydney, Australia, told The Guardian. "If insect species losses cannot be halted, this will have catastrophic consequences for both the planet's ecosystems and for the survival of mankind."

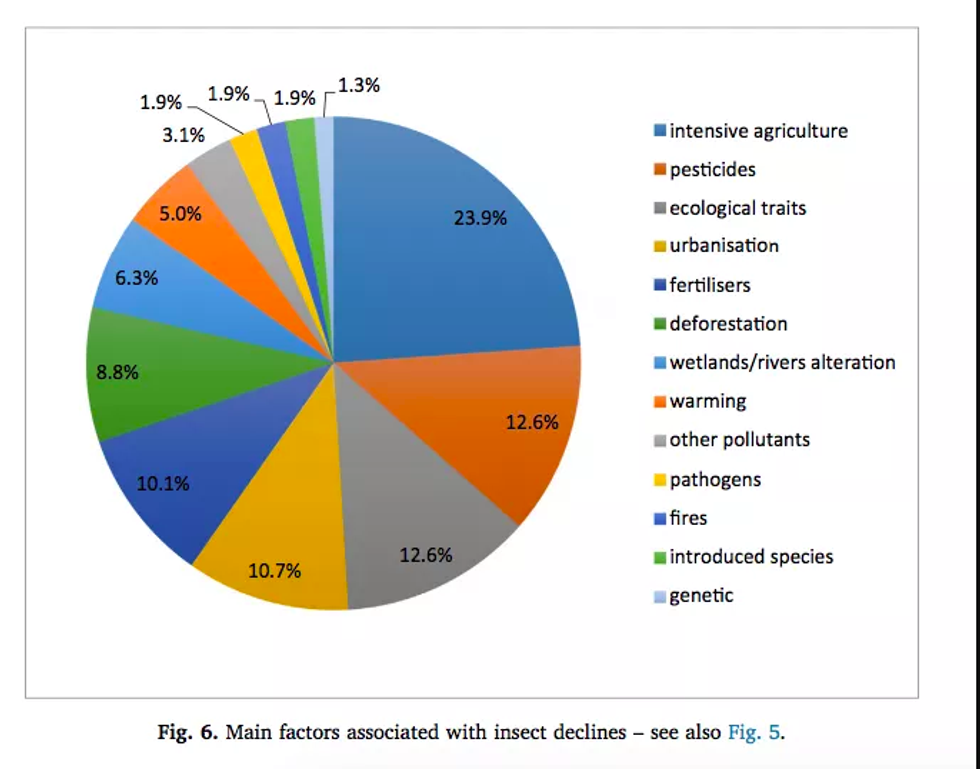

Habitat loss is largely responsible for the decline in insect populations. Pesticides, climate change, and invasive species all play a significant role in hastening the decline, too.

"Unless we change our ways of producing food, insects as a whole will go down the path of extinction in a few decades," the review's co-authors wrote. "The repercussions this will have for the planet's ecosystems are catastrophic to say the least."

The researchers note:

The repercussions this will have for the planet's ecosystems are catastrophic to say the least, as insects are at the structural and functional base of many of the world's ecosystems since their rise at the end of the Devonian period, almost 400 million years ago.

People responded with alarm:

The study is imperfect, however. Scientists do not know how many species of insect exist and lack adequate population data for all of them. Much of the data also comes from "developed" countries like the United States and those in Europe. The study lacks information from tropical regions, which are areas where new species of insect keep being discovered.

As a result, people like scientist and researcher Christian Schwägerl responded with skepticism.

The Guardian, the first publication to report the news, later posted a grave warning from its editorial board that serves as an indictment against what they refer to as "unchecked human greed":

The chief driver of this catastrophe is unchecked human greed. For all our individual and even collective cleverness, we behave as a species with as little foresight as a colony of nematode worms that will consume everything it can reach until all is gone and it dies off naturally. The challenge of behaving more intelligently than creatures that have no brain at all will not be easy. But unlike the nematodes, we know what to do. The UN convention on biodiversity was signed in 1992, alongside the convention on climate change. Giving it the strength to curb our appetites is now urgent. Biodiversity is not an optional extra. It is the web that holds all life, including human life.

The clock is ticking.

@elxavipapi/Instagram

@elxavipapi/Instagram r/TikTokCringe/Reddit

r/TikTokCringe/Reddit @deniscepalacios/TikTok

@deniscepalacios/TikTok r/TikTokCringe/Reddit

r/TikTokCringe/Reddit @deniscepalacios/TikTok

@deniscepalacios/TikTok r/TikTokCringe/Reddit

r/TikTokCringe/Reddit @deniscepalacios/TikTok

@deniscepalacios/TikTok r/TikTokCringe/Reddit

r/TikTokCringe/Reddit

@WhiteHouse/X

@WhiteHouse/X

@carol_haynes_/Instagram

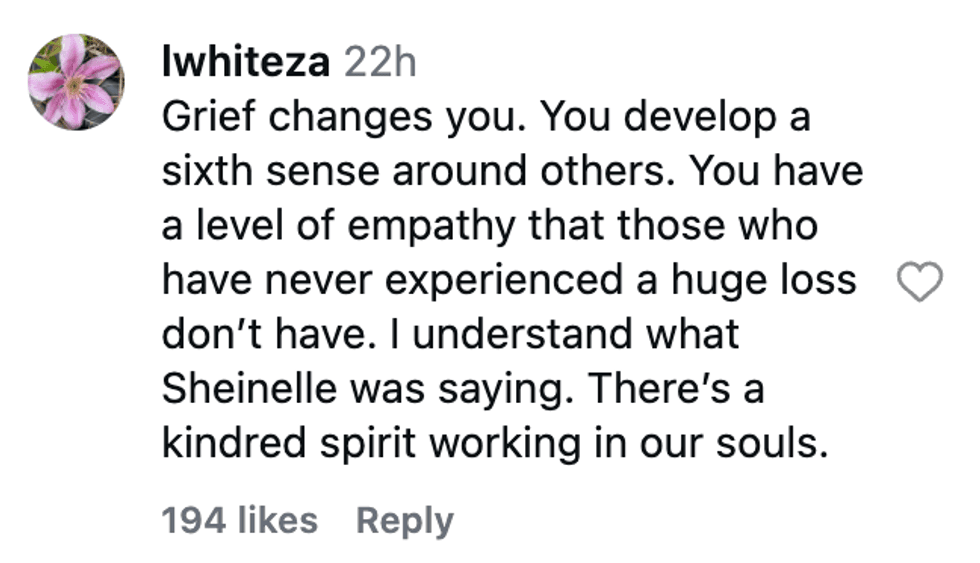

@carol_haynes_/Instagram @lwhiteza/Instagram

@lwhiteza/Instagram @iamdrkandace/Instagram

@iamdrkandace/Instagram @solveigerway/Instagram

@solveigerway/Instagram @sziulkow/Instagram

@sziulkow/Instagram @claudiatorres2019/Instagram

@claudiatorres2019/Instagram @carolken/Instagram

@carolken/Instagram @karenpayton34/Instagram

@karenpayton34/Instagram @mamaburnside/Instagram

@mamaburnside/Instagram @alr_thrives/Instagram

@alr_thrives/Instagram @dr.rxq/Instagram

@dr.rxq/Instagram @bogie1954/Instagram

@bogie1954/Instagram